An interdisciplinary team of researchers in Auburn University’s MRI Research Center, located within the Samuel Ginn College of Engineering is using a technique called functional magnetic resonance spectroscopy to study the biochemistry of people with post-traumatic stress disorder.

The goal of the project is to understand better the neurobiological basis of working memory deficits in people with PTSD, a disorder that affects an estimated 24.4 million Americans, according to the nonprofit PTSD United. PTSD causes anxiety and flashbacks triggered by a trauma, such as combat exposure, sexual violence or an accident.

In addition to feeling afraid or stressed, people with PTSD also commonly report difficulties with concentration, attention or memory.

“I’m particularly interested in those cognitive impairments, and I would like to better understand them so that we can find ways to treat them,” said Meredith Reid, the project’s principal investigator and a research assistant professor in electrical and computer engineering.

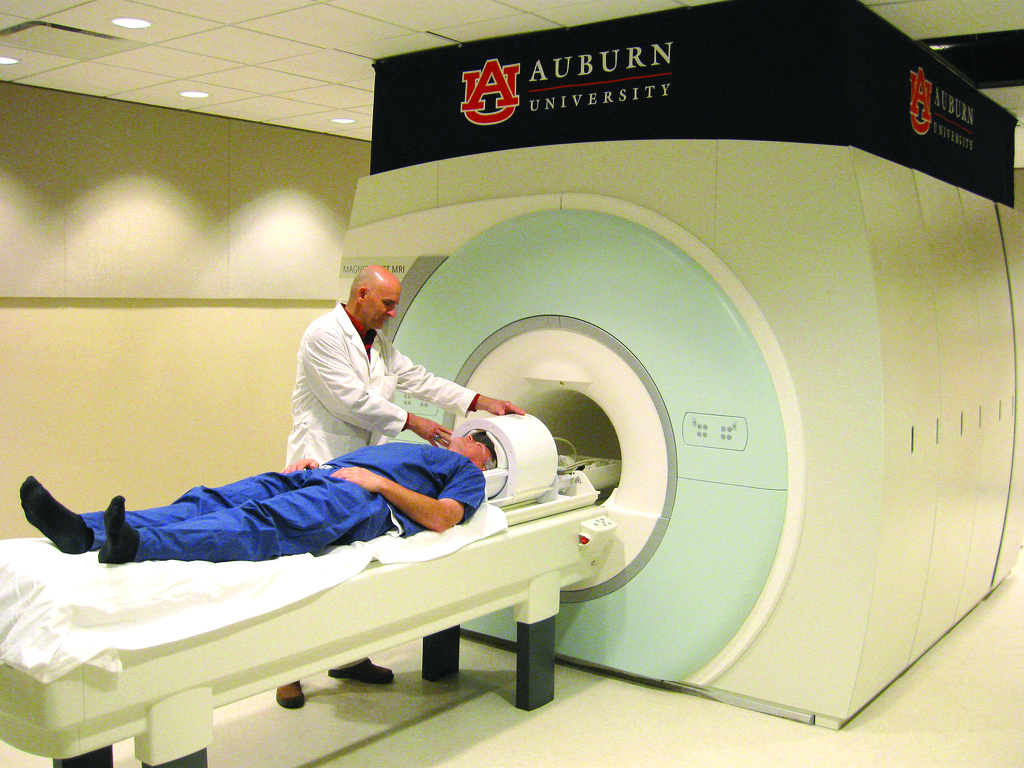

Auburn’s state-of-the-art MRI Research Center is home to one of the first actively-shielded whole-body 7 Tesla MRI scanners available for research use in the United States. Reid says the 7T scanner is ideal for this study because it is more sensitive and better able to detect metabolites in the brain and how they vary over time.

“We know from functional MRI that people with PTSD have reduced brain activation during cognitive processes, and there’s some evidence of a neurometabolic abnormality, but no one has determined whether these two are related,” Reid said. “Functional MRS and the 7T here at Auburn will help us address that.”

Led by Reid and Auburn psychology faculty Jeff Katz and Frank Weathers, the study will be conducted by performing functional MRS scans on 60 subjects divided among three groups. One group will include people with a clinical PTSD diagnosis, and the second group will include those who underwent a traumatic event but did not develop PTSD. The third group of subjects will not have experienced a traumatic event.

“The study volunteers will undergo a brain scan while they are performing a working memory task,” Reid said. “For example, they will see a series of letters on the screen and they will have to decide if the current letter is the same as the one they just saw. And while they’re doing that, we will measure the metabolites in their brain and look for how it changes during the memory test.”

In the short term, the researchers hope to discover how PTSD affects working memory, but a long-term goal is to use the research as a basis for developing new

medications to treat with PTSD.

The study is a four-year project supported by a $623,854 grant from the National Institute of Mental Health.