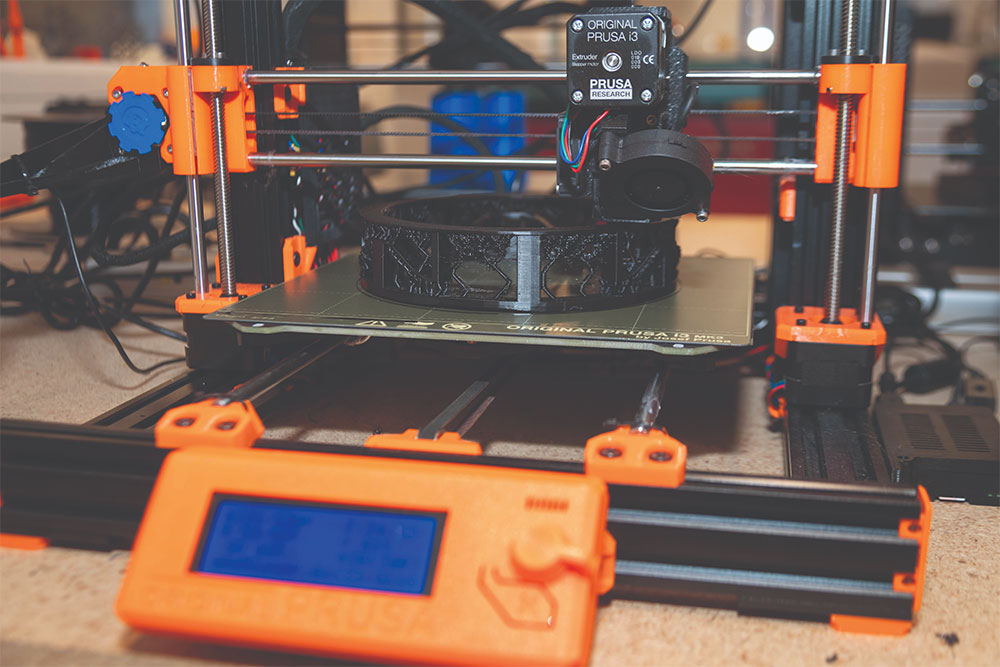

Right now, there are at least 90 3-D printers on Auburn’s campus — that’s the official number on the spreadsheet Mike Ogles put together back in late March. There’s 13 in the maker spaces inside the Brown-Kopel Engineering Student Achievement Center, two in the Auburn University Biomechanical Engineering lab.

And, of course, there are plenty over in the Gavin Engineering Research Laboratory at the National Center for Additive Manufacturing Excellence (NCAME) where Ogles, director of NASA programs for the Samuel Ginn College of Engineering, also serves as associate director for business development. It adds up fast.

Ogles had been thinking about conducting a census of professors and researchers who had access to 3-D printers for a while. For a school that, thanks to NCAME, has quickly established itself as one of the additive manufacturing research and development capitals of the world, establishing even just a loose network of faculty with additive capabilities, however sophisticated, made sense.

But he never got around to it. Things happened, like they always do. People get busy, projects get tabled, pandemics shut down the world.

“But, you know, that’s the irony,” Ogles said. “COVID-19 obviously put plenty of campus initiatives on hold. But it actually helped launch Auburn Makes.”

It started with a phone call.

“Gov. Ivey’s office contacted us, basically wanting to know how many 3-D printers the college had access to in case they needed to martial them into service to compensate for possible personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages,” said Steve Taylor, associate dean for research in the Samuel Ginn College of Engineering. “They were preparing for the worst.”

As soon as he hung up with the governor’s office, he dialed Ogles.

“He said ‘Mike, remember that project you wanted to work on with the 3-D printers? Well, we need you to do it — quickly,’” Ogles said. “In a day and a half I’d found 85.”

And, as fate would have it, some were already being put to emergency use.

Harnessing Expertise and Resources

Over the weekend of March 20, a team of mechanical and electrical engineering faculty conceived and tested the RE-InVENT, a device that could quickly and inexpensively convert CPAP machines into ventilators, which hospital administrators feared could possibly be in short supply in the early days of the pandemic.

Research engineer Garon Griffiths, who oversees the maker spaces in the new Brown-Kopel Engineering Student Achievement Center, is quick to downplay his role in developing the innovation. Michael Zabala is quick to celebrate it.

“We really needed adapters so that we could plug in a pressure gauge for the RE-InVENT,” said Zabala, assistant mechanical engineering professor. “Ordering them would have taken too long, so Garon volunteered to print them for us.”

The RE-InVENT went on to receive national attention and was submitted for FDA approval.

“Garon is a good example of the volunteerism that was motivating a lot of our faculty in those uneasy first weeks of the pandemic,” Taylor said. “Tom Burch and Michael Zabala had just begun their incredible work on the RE-InVENT when we got the call from the governor’s office, but several others were also answering their own call-to-arms. Garon was kind of a utility player, using the 3-D printers in Brown-Kopel to facilitate a lot of what was happening. It was very much an all-hands-on-deck situation.”

Two of those hands belonged to Griffiths’ fellow research engineer Christian Brodbeck, who as advisor to the Auburn chapter of Engineers Without Borders, is no stranger to volunteering his time.

In late March, Brodbeck and engineering safety manager Emmanuel Winful spearheaded a massive drive to collect and deliver campus donations of gloves, goggles, lab coats, face masks, hand sanitizer and other PPE to East Alabama Medical Center (EAMC). He also helped coordinate the effort that truly demonstrated the problem-solving potential of harnessing the college’s expertise and resources.

“When we took what we’d collected to EAMC, we realized that they were also really in need of face shields,” Brodbeck said. “With a new understanding of all of the 3-D printing capabilities that we had, we knew that was something that we could definitely work on. No one wanted to just be sitting there. We wanted to be doing something.”

For the next few weeks, Brown-Kopel became the capital of “Doing Something” at Auburn University.

“Mike Ogles gave me the spreadsheet, and we asked those on campus with a 3-D printer if they could spare one so we could start printing face shield frames,” Griffiths said. “If they said ‘yes,’ we distributed the parts file that we had downloaded.”

The campaign cranked into high gear, but occasionally had to get lo-fi.

“It was pretty obvious that just a frame wouldn’t do much to stop the spread of the virus,” Brodbeck said. “We obviously wanted to provide the actual shields as well, but in the spring, the polycarbonate material that they’re made from was in really high demand. Everybody was trying to get it. So we improvised.”

You’re welcome, Office Depot.

“Yeah, we wound up using overhead projector sheets,” he said. “They weren’t ideal, but they did the trick in a pinch. We hit pretty much every office supply store in town and purchased thousands of them.”

And thousands of rubber bands.

“The back strap of the regular shields was elastic, but elastic was another material that was in short supply,” Brodbeck said. “Rubber bands would kind of pinch, but they also worked in a pinch. They at least held it to your face.”

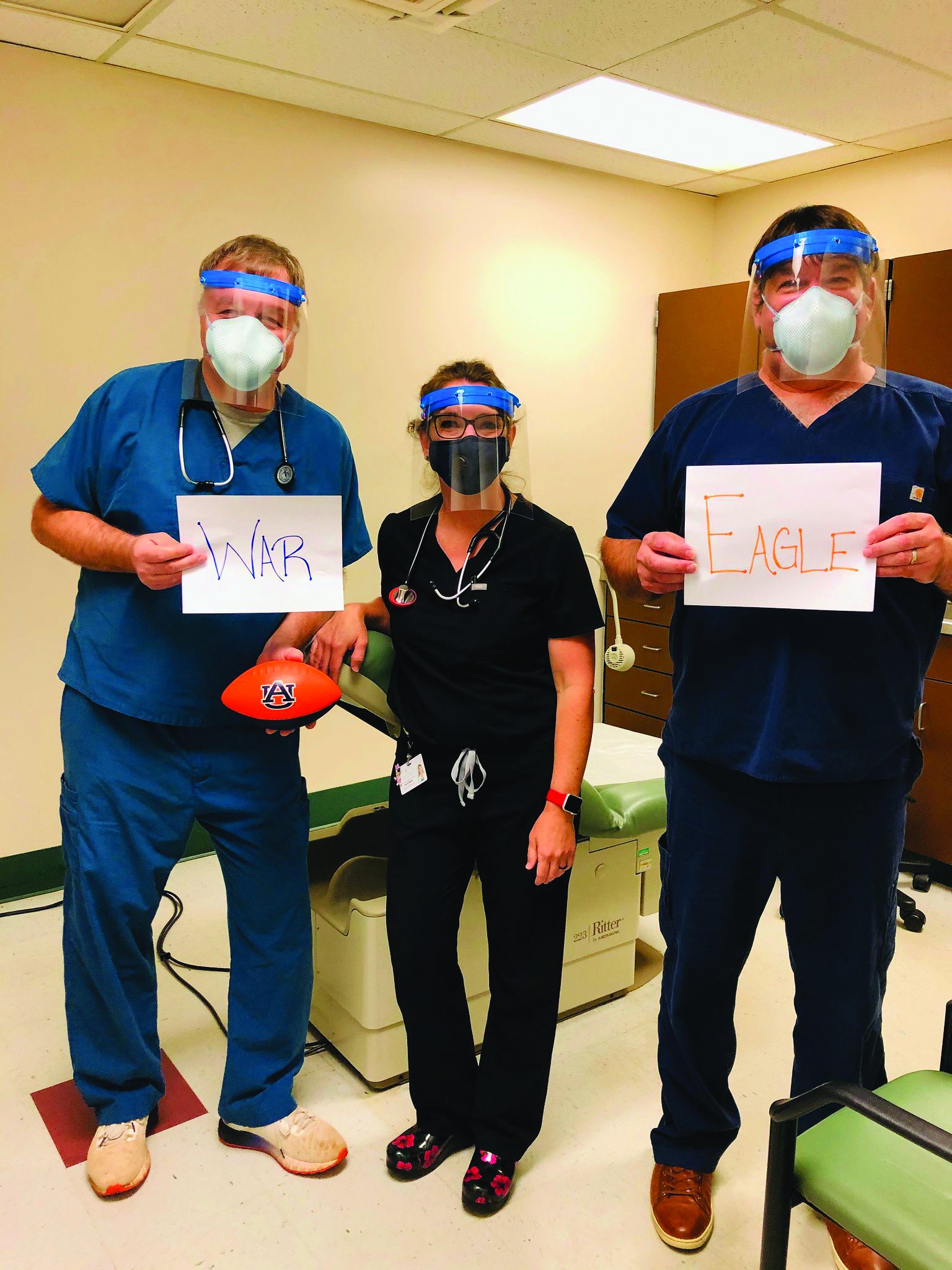

After assembly came distribution. Most shields were slated for EAMC, but word had gotten around — running low on face shields? Call Auburn.

Requests poured in from medical and dental clinics across the state and region, and even the Alabama Department of Corrections. Thousands of masks were produced and delivered in boxes that included information about the production process — and a copy of the Auburn Creed.

“The whole idea,” said Eldon Triggs, a lecturer in aerospace engineering who lent his laser-cutting services to the face shield effort, “was to put Auburn’s principles into practice, especially during this really critical time.”

However, by mid-spring, the urgency surrounding PPE supply was beginning to wane. The promise demonstrated in the incredible collaboration, however, was growing more and more apparent.

“Steve Taylor wondered what we could do if we kind of got the band back together before it really broke up, and also tried to bring in some others from across campus,” Ogles said. “It seemed like the natural thing to do. That we could continue to make a difference by pooling all the expertise and resources at Auburn’s disposal just seemed obvious, whether it related to fighting the virus or not.”

“Well, America Makes is a national leader in additive manufacturing innovation being the flagship of the National Network of Manufacturing Innovation Institutes, and they are funding several research efforts at Auburn University in additive manufacturing,” Taylor said. “They’ve recently been heavily focused on connecting medical providers in need of PPE with manufacturers with 3-D printing capabilities. So calling what we were doing Auburn Makes seemed like a perfect choice.”

Next, they needed a mission statement. Enter Jerrod Windham, an associate professor in the School of Industrial and Graphic Design who had enthusiastically volunteered his 3-D printers for the face shield effort, and ultimately volunteered to articulate Taylor’s vision.

Auburn Makes provides makers, and those who wish to be, a path to transform ideas into reality. Auburn Makes is an inclusive network of makers and fabrication resources with the goal of fostering innovation, ingenuity and creativity through the collaborative, hands-on exploration of advanced manufacturing technologies. Auburn Makes is not housed in any one college or department of Auburn University, but exists to bridge those traditional boundaries and, therefore, is available to all active Auburn students, faculty, and staff interested in further developing creative problem solving and leadership skills.

“I think Jerrod captured it perfectly,” Ogles said. “Once we had a defined direction with the sort of difference we were looking to make, we tried to hit the ground running.”

And, at first, it was pretty familiar ground. Over the summer, Brodbeck and Griffiths once again fired up the network of printers to produce face shields, this time for Auburn faculty.

Through a refined process — and, finally, with actual polycarbonate — 3,000 face shields were produced at a rate of 100 per day.

“Those,” said Brodbeck, “we were a little prouder of.”

But he probably takes the most pride in the group’s most recent major undertaking — the plexiglass partitions installed throughout public spaces across the engineering campus to provide students, faculty and staff an extra barrier of protection against viral spread.

“We needed to do it quickly,” Brodbeck said. “We looked at buying them, but we realized we could make them at a fraction of the cost. Steve Taylor sent me a picture he had found on Twitter from another SEC school that had partitions held together with blue painters tape. He said, ‘Whatever we do, let’s make it a little more advanced than that.’”

So, instead of heading to Home Depot, Brodbeck went to the Department of Aerospace Engineering — specifically the lab of assistant professor Vrishank Raghav.

“We tested air flow over several designs, and it turned out that the optimal design for, say, deflecting a cough, was actually a straight partition,” Brodbeck said. “Having Vrishank’s expertise was invaluable.”

In just three weeks shortly before in-class instruction resumed, the college was able to produce and install 120 partitions, all held together not with painters tape but 3-D printed brackets bearing the name Auburn Makes.

Taylor can’t wait for what’s next.

“I think Auburn Makes is going to be something that can really make an impact,” he said. “By branding and building on the spirit and brainpower behind those early efforts — things like the facemasks and RE-InVENT — we’re hoping to establish a permanent presence that can serve as a resource for students and anyone at Auburn looking to see an idea or a prototype to fruition.”

Including Taylor, Ogles, Brodbeck, Zabala, Griffiths, Triggs, Windham, Jordan Roberts, who runs the Department of Mechanical Engineering’s Design and Manufacturing Lab, and James Johnson, another research engineer in biosystems engineering, Auburn Makes now boasts 17 experts from across Auburn University — from engineering to industrial design, from the Athletics Department to the Ralph Brown Draughon Library. The group holds weekly meetings, and recently launched an interactive website that Ogles hopes will help truly tap the initiative’s potential.

“The site features a map that shows all of the equipment and expertise we have at our disposal,” Ogles said.

Need help? Need a lathe? A laser-cutter? Submit a request. Need a 3-D printer? Get on the map, see which one is closest, and hit submit.

Sort of like Uber for additive manufacturing services?

“Well, I guess you could think of it like that. But at the same time, Auburn Makes is not just 3-D printing,” he said. “A lot of the pioneering projects obviously were additive manufacturing focused, but the scope is now a lot larger than that. We can offer access to a lathe, we can do laser-cutting. Thanks to Dana Marquez in the Athletics Department, we even have a sewing machine.”

He paused.

“But yeah, OK,” he said. “We definitely have a lot of 3-D printers.”