In 2012, Auburn University acquired the nation’s third actively shielded whole-body 7 Tesla MRI.

The $8.5 million machine — still one of just seven in the South — provided Auburn University’s MRI Research Center game-changing access to dimensions of detail once unimaginable in cognitive neuroscience and brain imaging.

Eight years later, the Samuel Ginn College of Engineering remains a national leader in medical imaging research.

The director of Auburn’s first electrical engineering laboratory would be proud.

On Friday, Nov. 8, 1895, as Auburn’s football team rode north to Nashville for its inaugural game under head coach John Heisman, the world changed. Word of what German mechanical engineer Wilhelm Röntgen had first seen in his laboratory — that morning in America, that evening in Würzburg — began popping up across the Atlantic the first week of January 1896. Newspapers began running brief but tantalizing tales about some sort of “new photography.”

There had been a blurb on the supposed discovery in the Saturday, Feb. 8, 1896, edition of The Atlanta Constitution. And Anthony Foster McKissick had laughed.

For 24 hours, he thought it had to be a mistake, a miscalculation. Maybe even a misprint.

Then came Sunday.

There was an abridged account of a Harvard professor’s replication of Röntgen’s experiments under the headline: “A Giant Stride in Science: How Objects Are Photographed Through Opaque Bodies – The Cathode Ray.” It was almost too fantastic to believe. McKissick read the story. He read it again. He read it to his wife. She saw the look in his eyes. So did his students.

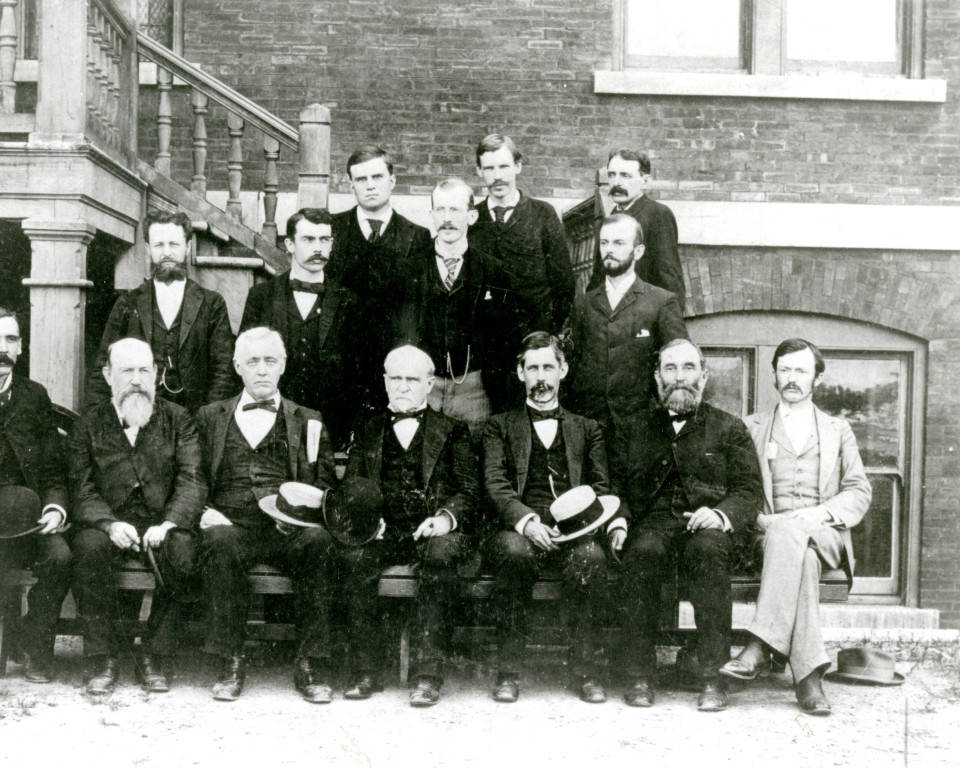

In 1891, Alabama A&M president Leroy Broun had hired the 23-year-old McKissick to take charge of what the school was calling the first electrical engineering department in the south. He’d graduated with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in engineering from the University of South Carolina in 1889, and had spent the past two years in pivotal positions at Westinghouse Co. and the Congaree Gas and Light Company, the first electric company in Columbia, S.C.

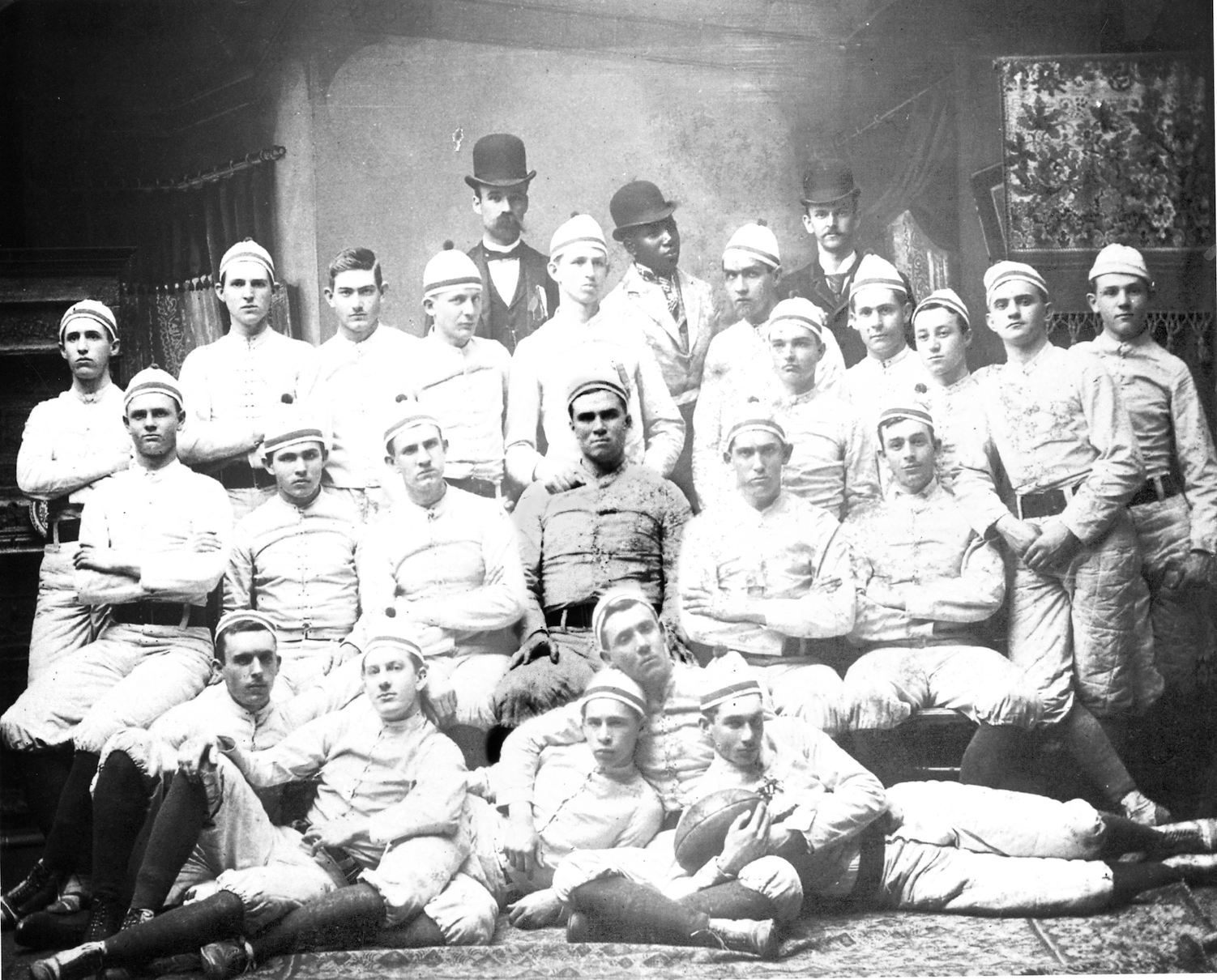

His position on the gridiron was just as pivotal. At 6’0, 210 pounds, McKissick was easily the biggest man on Auburn’s first football team — professors were permitted to play in those early years — and the natural choice for center in 1892. He was good. He loved the game. He loved science more.

What he couldn’t get out of his mind as he hurried from his home on South Gay Street to the electrical laboratory in the basement of Samford Hall on Monday morning, Feb. 10, 1896, were the bones of Röntgen’s wife’s hands. The papers said the barium platinocyanide screen actually captured the shadows of her metacarpals and phalanges, wedding ring and all.

He looked in the corners and under tables. He finally found several vacuum tubes just sitting around, just waiting for a wizard to fill them with a new form of energy. He settled on one of the pointed four-inch Crookes tubes containing tiny platinum wires, same as Röntgen had reportedly used. That was the easy part. The electricity was where things would get interesting.

He told his students the amount of power needed could, were they to join hands, instantly kill half of them. No one flinched. It was going to be a fun week.

They spent most of Monday building a new alternator. When they finished, they cranked 100 volts into the high frequency Tesla induction coil that the students had built that past fall. Suddenly, they had 15,000 volts. They then sent that bolt of lightning through a spark-gap and a condenser and turned it into a casket-friendly 100,000 volts. McKissick held a five-inch piece of wood to the cylinder. It burned in two. That was enough fun for Monday.

On Tuesday, it was time. They connected the new alternator to the Crookes tube, stood back, and threw the switch. The platinum wires sizzled. The tube filled with a soft, glowing white light that only a handful of Americans had ever beheld. This was it. They now shared the room with an invisible force that the world was calling X-rays.

McKissick didn’t know much about photography. But he was pretty sure he had some photographic plates lying around. He found a box of Seed’s Extra-Rapid Dry Plates buried in the lab. They’d been there for at least two years. He dusted one off and slipped it into a plate holder. He looked around for a test subject. His eyes settled on a small saw. He put it on top of the photographic plate, then covered it with a thin wooden board. He picked everything up and placed it beneath the glowing tube. They watched and waited.

After two and a half minutes, they removed the plate and carried it to a makeshift dark room.

The outline began to appear almost immediately. Without a camera, and through solid wood, they had photographed a saw.

McKissick couldn’t believe it. He was beaming. His students were beaming. The tube was beaming. They shut off the power. One of the students immediately took off for the post office to wire Atlanta for fresh plates. Until they arrived, McKissick thought he could borrow some from Mr. Abbott, the Loveliest Village’s resident photographer. If no one was sitting for a portrait, surely he could spare some in the name of science. Absolutely, Abbott said.

The original board the class had used to obscure test subjects was less than an inch thick. On Wednesday, they went with something thicker and denser. It made no difference.

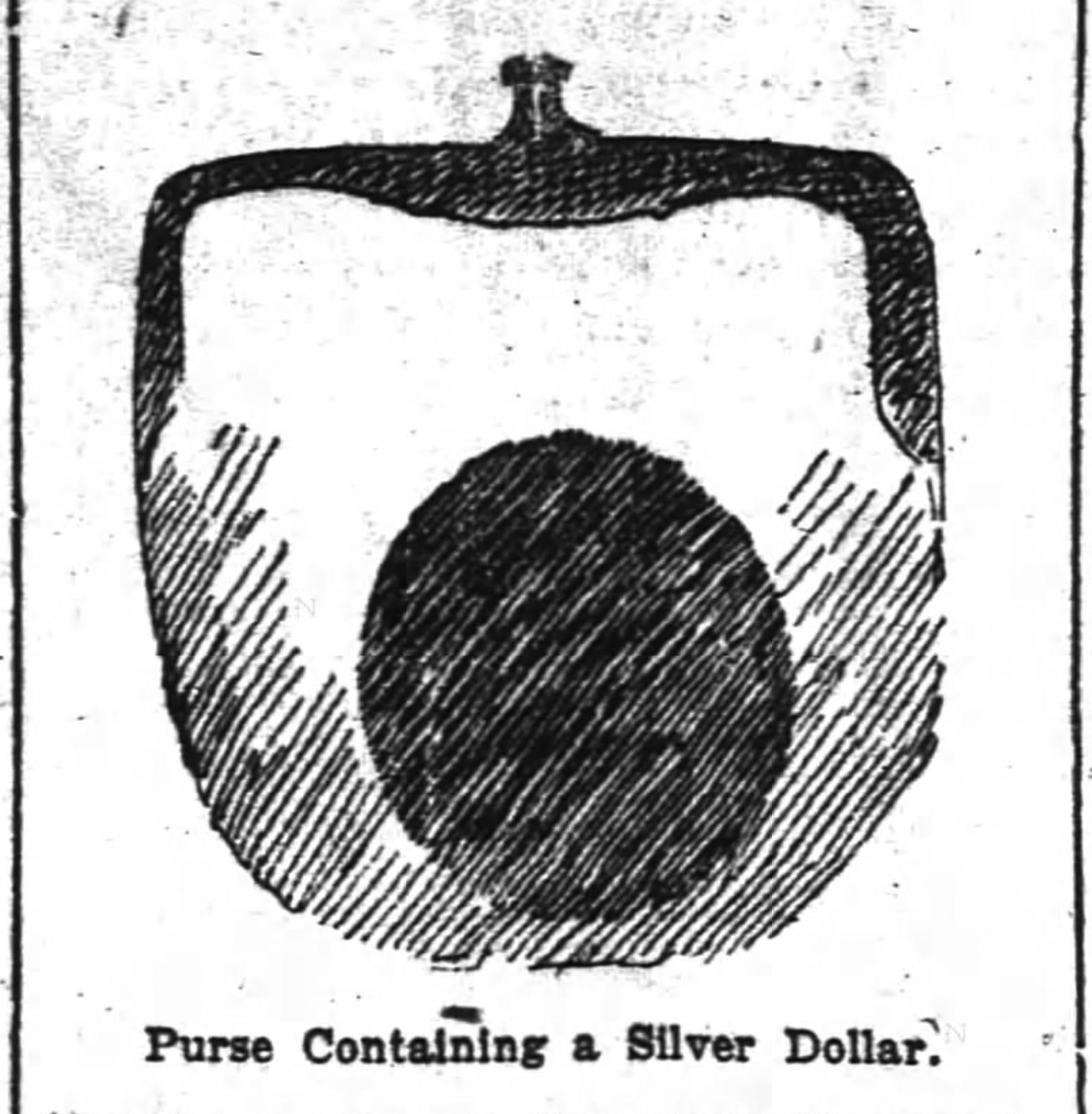

The outline of the scissors, blades open, was perfectly clear. So was the dollar inside the change purse.

They put a clasp and a key inside a cardboard box. Miller Reese Hutchison, one of McKissick’s star students, and later chief engineer for Thomas Edison’s laboratory, took the plate into the dark room and grabbed the bottle of Rodinol.

Jaws dropped. It was as if the box hadn’t even been there.

But nothing prepared them for the bones.

McKissick would have done it himself were there not any takers. But there were plenty. Hands shot into the air. He examined them, looking for the most scientifically interesting. He settled on a boy with a right index finger bent oddly to the left, hoping to capture as many clearly defined twists and turns and abnormalities as he could. Because his mind was already there — surgeries! Fractures, breaks, bullets! Under the Röntgen rays, in theory, you could locate them instantly.

He had the boy stand as far back as he could while keeping his hand still on the plate. McKissick flipped the switch. Eight minutes later, he flipped it off.

The negative image was perfect. They saw the faint outline of the flesh. They saw the dense darkness of the bones. They heard the reverent silence of the room at the advent of a miracle.

Word traveled fast.

A.F. McKissick, the South’s premiere practitioner of the new photography! One of the country’s most experienced Röntgen ray exhibitionists!

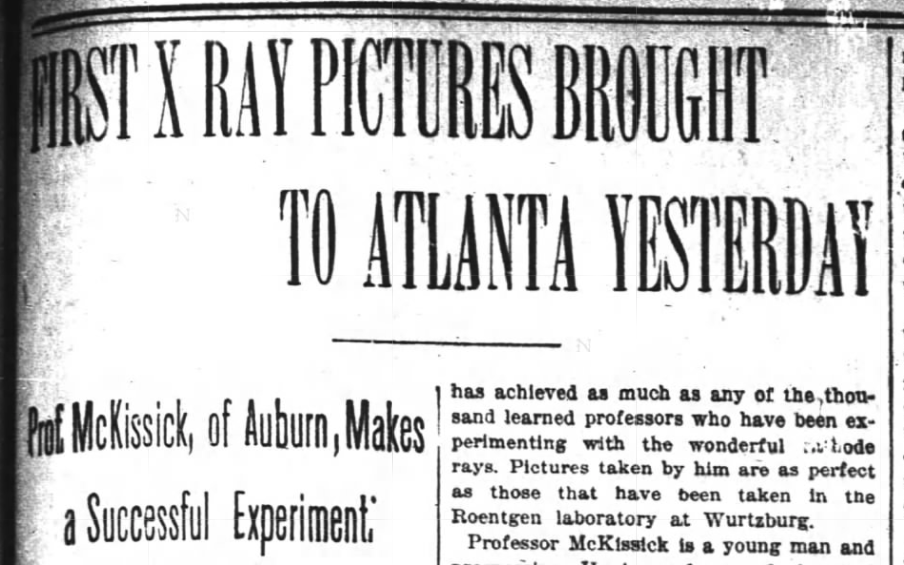

The coverage started in the Constitution and didn’t stop.

On Thursday, he’d quickly carried 15 or so of his best plates with him to Atlanta and dazzled the Constitution’s newsroom with the results of, as the paper called it, “the new light.” They gave him nearly half a page — illustrations of the plates, even his portrait — under the headline “First X Ray Pictures Brought To Atlanta Yesterday!”

The Opelika Post was eager for its own peek at the rays as soon as he returned.

So was a writer from a leading southern scientific journal. McKissick opened up the lab and obliged them, same as he would for hundreds more over the coming months.

He was already an old pro at scientific demonstrations. Not two weeks earlier, he’d once again shown off some of his favorite experiments during yet another campus lecture on Nikola Tesla.

He made sparks jump between friends and lit up wires formed to spell the engineering genius’ last name.

But the X-ray was now the show-stopper. The finale was always the inside of the hand. It was sorcery.

McKissick mania continued through the spring and well into the summer. Within a few days of the Constitution’s story, he’d become a regional celebrity, not just a feather in Auburn’s cap — a plume: the captain of the cathode, a name to know and revere, “an Apostle of Science,” The Birmingham News proclaimed.

To celebrate George Washington’s birthday, Birmingham’s school children were instructed to write McKissick’s name on the board next to Röntgen’s as a tribute to a southerner who was, in the field of science, currently honoring the first president’s legacy of leadership perhaps more than any man in America.

One rival institution was not amused.

The University of Georgia did its best to keep up, boasting that X-ray experiments conducted by its professors deserved equal attention.

McKissick’s name remained the biggest by a mile and, as a result, earned him the biggest toys.

Companies began showering him with gifts and equipment. Boston-based L.E. Knolt Apparatus Co. delivered the finest Crooke’s tube available, by which McKissick, with only a five-minute exposure, produced perhaps the clearest picture of the inner hand in the world at the time. Two voltmeters came from the Weston Electrical Instrument Company in Newark. Four transformers from the Water, Light and Power Company of Anderson, South Carolina. But what really turned the electrical lab into a revolving door of local curiosity seekers was the fabulous fluoroscope from the Edison Manufacturing Co.

Rather than waiting on a static image to develop, the handheld “Edison Glasses” gave operators a fluid, miraculous peek at whatever part of the body they were trained on.

McKissick was an engineer, but the medical application of the rays had been obvious from the second he saw inside one of his students, and Edison’s ingenious new apparatus was the quickest way to embrace it. People left his lab rubbing their eyes, shaking their heads, declaring the discovery of the X-ray the greatest of the century.

McKissick took the show on the road, certain that the surgeons of the South would feel the same. Fluoroscope in hand, he moonlighted as a miracle worker for the rest of the spring and summer, volunteering his X-ray vision to the public, inviting bullet-ridden strangers to come find salvation under Auburn’s magic light.

He promised that he could “locate bullets or any metallic substance, or show fractures of the bones in any part of the limbs of the body” for anyone who could travel to the electrical lab accompanied by a physician. They came from all over. A doctor from Columbia, Alabama, brought a teenager who’d suffered 13 years with a pistol ball somewhere behind his knee cap; McKissick lit up the device and found exactly where it was in seconds. A doctor from Sylacauga did the same thing for a child crippled for 18 months after being accidentally shot in the leg. Thanks to McKissick, the child would walk again. The possibilities were endless.

“I see no reason,” McKissick even told the Constitution, “why the light cannot be used to photograph the brain.”

The first director of Auburn University’s first MRI Research Center is proud.

“Wow,” said Tom Denney, director of the MRI Center and professor of electrical and computer engineering. “That’s amazing. As a fellow electrical engineer, I’m honored to play a part in Prof. McKissick’s legacy.”

He’s not just saying that. Thanks to a breakthrough gene therapy vector recently developed through brain metabolite testing under Auburn’s 7 Tesla, a 10-year-old child named JoJo suffering from a rare genetic nerve disease may walk again.

“Obviously, I’ve known we’ve been conducting some of the most advanced medical imaging research since the 7 Tesla arrived,” Denney said. “But that Auburn actually helped pioneer biomedical engineering? That’s really something to celebrate.”