Easily one of Auburn University’s most ingenious contributions to the fight against COVID-19, the device had performed flawlessly in early benchtop testing, starting with the proof of concept experiment in Zabala’s garage. But the April 3 test at Auburn’s College of Veterinary Medicine’s Vaughan Large Animal Teaching Hospital would determine whether the RE-InVENT would move from prototype into production.

That the machine kept a 200-pound goat with a lung capacity similar to that of humans properly ventilated for two hours validated its design in ways that even surprised Wood, who monitored the procedure via Zoom along with other anesthesiologists, including an associate professor of anesthesiology in Auburn’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

“It performed perfectly,” Wood said. “It went better than I expected in being able to ventilate the animal.”

A subsequent successful live animal test, this time on a sheep, proved just as promising. After that, it didn’t take long.

“While many companies across the country are building ventilators, we thought few could assemble and produce the needed devices in under a week,” Hill said. “Once the successful animal test was completed, IS4S immediately began taking the steps to fabricate the units for distribution.”

IS4S has fielded requests for the innovative accessory from across the country and as far away as India.

“We have several rural hospitals asking when we can send them devices,” said Glenn Rolander, IS4S president and CEO. “There’s also been a strong international demand from multiple medical agencies that contact us almost daily.”

While the RE-InVENT awaits Emergency Use Authorization approval from the FDA that would allow distribution of the device to health care professionals in rural areas, IS4S is endeavoring to provide units to Family Legacy Missions, a medical ministry serving vulnerable children in Zambia that expects its number of COVID-19 cases to rise over the summer.

“These are difficult times,” Burch said. “Everybody who understands the gravity of the situation wants to do something to help, so it feels good to think you’ve helped with something that may have an impact.”

Burch’s former student agrees.

“Wait, did I have you in a class?” Burch said to Zabala minutes after the RE-InVENT’s first successful test in Zabala’s garage.

Zabala nodded and smiled.

“Got an A.”

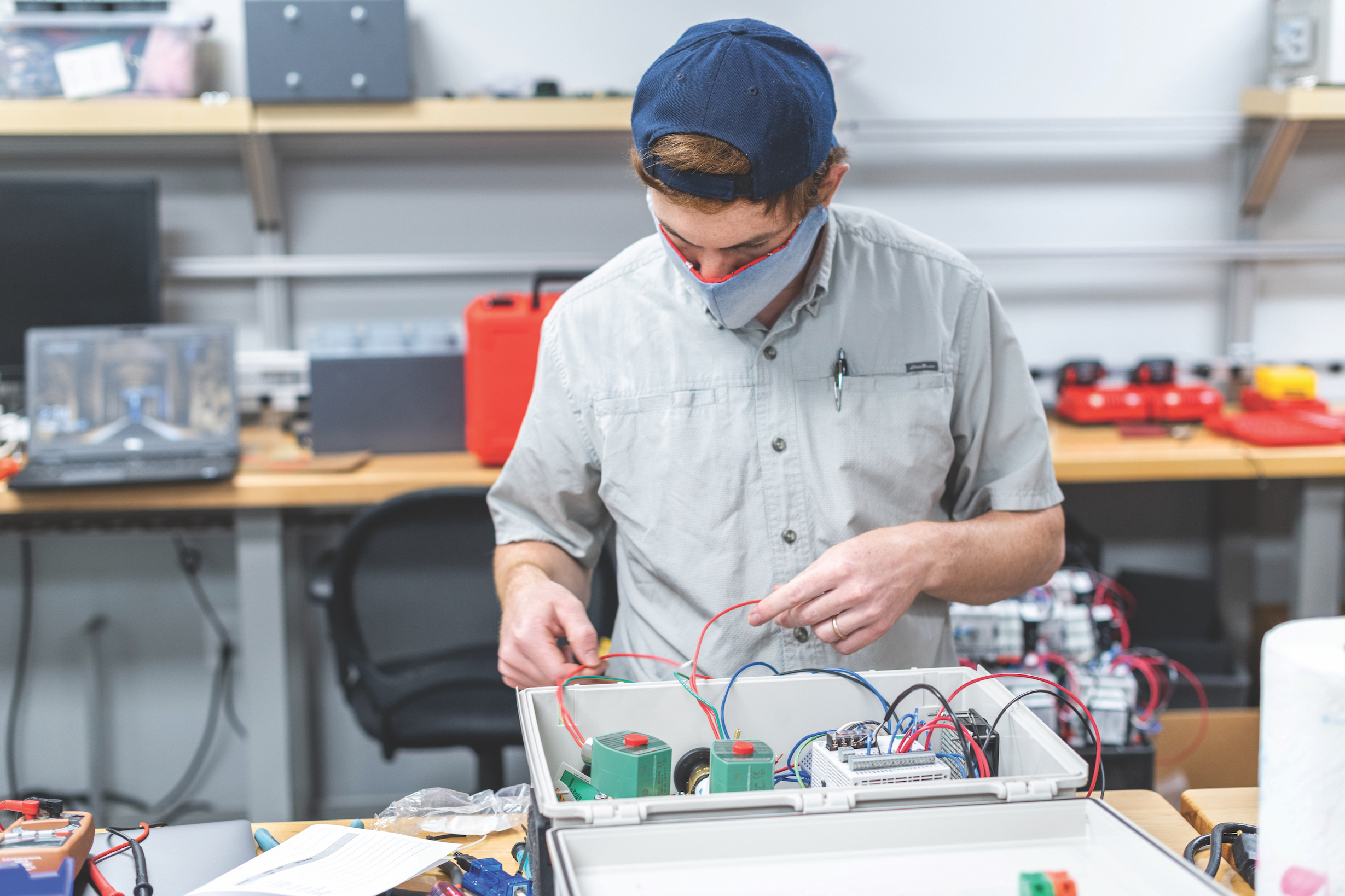

It was March 22. Chris Spiker didn’t have to guess which garage was Michael Zabala’s. On a normal Sunday afternoon, he might have thought he was looking at someone gearing up to mow the lawn. But during a pandemic? The guy in the medical mask bent over a work table covered in wires and tubes was a dead giveaway.

Spiker was finally heading home from his ICU shift at East Alabama Medical Center. He lived in Zabala’s neighborhood, so Glenn Wood, an anesthesiologist at the hospital consulting with Zabala on the RE-InVENT project, had asked him to go check it out — to make sure he wasn’t seeing things in the video Zabala had just texted.

Spiker parked on the street. He was still in scrubs. He introduced himself. No one shook hands. Tom Burch, a senior lecturer in Auburn’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, kept his distance, a bottle of sanitizer dangling from his belt. He’s in his 60s. Zabala, an assistant mechanical engineering professor is only in his mid-30s, but he’d been just as cautious as Burch. He’s taught on the biomechanics of respiration in his Auburn University Biomechanical Engineering (AUBE) lab. He knows how lungs work. He was learning how the virus worked.

Zabala got to it. He rattled off the Cliff’s Notes from the weekend, about the team’s desire to help mitigate any potential respiratory treatment equipment shortages in the early days of the COVID-19 crisis, about Burch’s suggestion to incorporate a CPAP machine, about the parts needed, about meeting Wood at Texaco that morning to grab some tubing and the test lung. Then it was time.

Burch flipped the switch. Click. The test lung inflated.

Click. It deflated. Click. Inflated, deflated. Click, click, click, click.

It had rained that morning. The sun was finally out. The subdivision was just coming to life. Moms pushing strollers looked over. Dads on golf carts stared.

So did Spiker.

Click, click.

“Does it have adjustable pressure settings?” Spiker said.

“Up to 5-25 centimeters,” Burch said.

Click, click.

“OK, it maybe needs to be about five at minimum, because that’s the baseline to overcome the tube that’s in their mouth. And you can adjust the rate, too?”

“Oh, yeah,” Zabala said.

Click, click. Click, click.

“Well, guys,” Spiker said, “I think you just created your own pressure-controlled ventilator.”

Unforgettable

The goat won’t remember April 3, 2020.

Zabala, Burch and the other Auburn engineers behind the RE-InVENT will never forget it.

“We had gone from concept to a successful test on a test lung in just two days,” Zabala, a 2007 Auburn mechanical engineering graduate, said of the device, which effectively converts a CPAP machine into a safe, emergency alternative to conventional ventilators. “But it was still just awesome to see it perform so well on the real thing.”

Burch, who earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mechanical engineering from Auburn in 1979 and 1982 respectively, agreed.

“We were pretty sure it would work,” said Burch, who first proposed incorporating continuous positive airway pressure to simulate a ventilator. “I use a CPAP machine, and it does 90% of what a ventilator does.”

The team focused on a design that would reliably ventilate a patient for an extended period, while also considering affordability and ease of manufacture.

“It was almost like something out of ‘MacGyver,’ or like that scene in ‘Apollo 13.’” said electrical engineering professor and RE-InVENT team member Mike Hamilton when he first learned of Zabala’s and Burch’s early efforts.

Thanks to control systems improvements from Hamilton, as well as computer-aided modeling assistance from team member and mechanical engineering lecturer Joe Ragan, the device can be assembled in as little as four hours using approximately $700 in readily available component parts in addition to a standard CPAP machine. Standard hospital ventilators can cost up to $25,000.

Easily one of Auburn University’s most ingenious contributions to the fight against COVID-19, the device had performed flawlessly in early benchtop testing, starting with the proof of concept experiment in Zabala’s garage. But the April 3 test at Auburn’s College of Veterinary Medicine’s Vaughan Large Animal Teaching Hospital would determine whether the RE-InVENT would move from prototype into production.

That the machine kept a 200-pound goat with a lung capacity similar to that of humans properly ventilated for two hours validated its design in ways that even surprised Wood, who monitored the procedure via Zoom along with other anesthesiologists, including an associate professor of anesthesiology in Auburn’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

“It performed perfectly,” Wood said. “It went better than I expected in being able to ventilate the animal.”

A subsequent successful live animal test, this time on a sheep, proved just as promising. After that, it didn’t take long.

“While many companies across the country are building ventilators, we thought few could assemble and produce the needed devices in under a week,” Hill said. “Once the successful animal test was completed, IS4S immediately began taking the steps to fabricate the units for distribution.”

IS4S has fielded requests for the innovative accessory from across the country and as far away as India.

“We have several rural hospitals asking when we can send them devices,” said Glenn Rolander, IS4S president and CEO. “There’s also been a strong international demand from multiple medical agencies that contact us almost daily.”

While the RE-InVENT awaits Emergency Use Authorization approval from the FDA that would allow distribution of the device to health care professionals in rural areas, IS4S is endeavoring to provide units to Family Legacy Missions, a medical ministry serving vulnerable children in Zambia that expects its number of COVID-19 cases to rise over the summer.

“These are difficult times,” Burch said. “Everybody who understands the gravity of the situation wants to do something to help, so it feels good to think you’ve helped with something that may have an impact.”

Burch’s former student agrees.

“Wait, did I have you in a class?” Burch said to Zabala minutes after the RE-InVENT’s first successful test in Zabala’s garage.

Zabala nodded and smiled.

“Got an A.”