The big engineering school in Texas had a cool space. Just not cool enough for Ethan Peat.

The mechanical engineering junior had thought about heading west after high school, same as his brother. But he wanted more freedom, more resources, more opportunities.

He’d grown up making anything and everything in the basement of his Nashville home: a built-from-scratch mini-bike; crazy, welded pieces of art, such as the steel dog for his girlfriend, Betsy. She loved gifts, but nothing from the mall, nothing from Amazon. If you were going to give her something, she wanted it to be from the heart. So that’s what he’d do — grab a welder and make her something from the heart. He enjoyed it. He never had to jump through any hoops. He never had to ask anyone’s permission. He wanted to keep it that way.

“I’d originally applied to another school, but their makerspace just seemed really restrictive,” Peat said.

Auburn’s didn’t. You signed up. You got trained. You had at it. When he thought about the next four years, that’s where he saw himself.

The only catch was that, technically, it didn’t exist yet.

In 2017, Auburn announced plans for the Brown-Kopel Engineering Student Achievement Center, a $44-million world-class facility that would boost Auburn’s commitment to providing the best student-centered engineering experience in the country by constructing the best on-campus active learning environment in the country.

There would be classrooms, a grand hall, computer labs, a cafe, tutoring services, a design studio.

But the 11,000-square-foot makerspace on the ground floor — officially dubbed the Design and Innovation Center — would be the crown jewel.

“A lot of big engineering institutions began building these sorts of facilities around that time as the maker movement was growing,” said Garon Griffiths, the center’s manager and 2003 Auburn mechanical engineering graduate who helped launch the Design and Innovation Center.

“As long as I’ve been around, Auburn engineers have been known for having strong, practical skills, and the Design and Innovation Center would solidify that reputation moving into the future,” he said. “That was a big idea behind it.”

The idea behind it was all Ethan Peat needed.

He’d first visited Auburn as a high school freshman. He liked it, but kept looking; when he came back the spring of his senior year, he stopped.

“Brown-Kopel still wasn’t even open, but when I saw the plans for the makerspace, that was it,” Peat said. “That’s why I chose Auburn.”

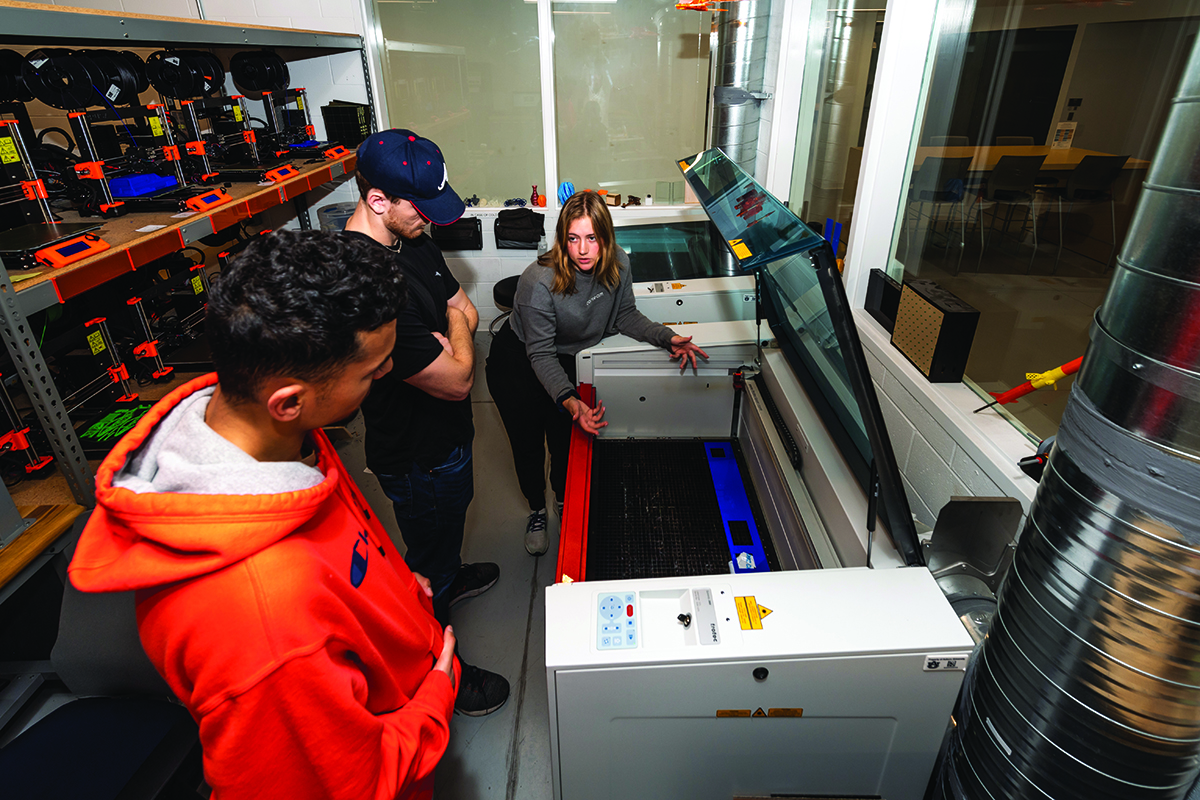

He is not alone. Go up to anyone at a repositionable workbench inside the Design and Innovation Center, and they’re either just like Peat, or knows someone who is. Take Olivia Viguerie, for instance. The chemical engineering sophomore is prepared to start a training session on the Trotec laser cutter. She’s from Hattiesburg, Mississippi. She’d planned on staying in-state for college. The makerspace changed her mind. So far, she’s only used it to add to the collection of custom pinback buttons on her blue jean jacket.

But that, she said before slipping on safety glasses, will change soon.

“At the time, (the Design and Innovation Center) wasn’t even something I imagined myself using that much,” she said, “but it showed just how much Auburn was doing for its students — that it’s doing everything to make sure they’d be successful engineers. It’s a big draw for people.”

Andrew McGill, engineering student services coordinator, starts nodding before you finish the question. Yes, absolutely, the room that takes up nearly half the floor beneath his office has made his job infinitely easier. Give the families the inside tour of Brown-Kopel and they’ll get a great view through the interior windows separating the makerspace from the computer stations. Take them outside, and they can peer through the four garage doors that open to a covered pavilion allowing work on large-scale projects.

“That’s the thing prospective students pay the most attention to,” McGill said. “You can kind of see it on their faces. It’s like kids in a candy shop.”

Only, it’s a woodshop, with Laguna Swift CNC (computer numerical control) routers that allow you to cut or engrave 2D and 3D designs into wood. And a prototype shop with one of the most precise laser cutters on the market and scores of Prusa i3 MK3S 3D printers running practically 24 hours a day, not to mention the Creality and Markforged machines. And an electronics shop with more varieties of microcomputers and micrometers and microcontrollers than a Radio Shack catalog.

And a metal shop with a Miller multimatic welder that can, as one student is demonstrating, shape steel into an electric scooter. And a machine shop, with a MAXIEM 1515 waterjet that can cut 4-inch thick metal (or granite or almost anything else, for that matter) with the highest nozzle horsepower on the market, plus the Vectrax lathe and CNC minimill that can chisel, say, Einstein’s face out of a chunk of aluminum.

That’s one of Cyrus Lloyd’s creations — one of the pioneers, the guy everyone points to. Want to talk to someone who takes advantage of the place more than anyone? Talk to Lloyd. Want to talk to someone who’s probably there right now? Find Lloyd, he’s around. Want to see someone building a machine that produces parts with sub-micron form accuracy and single digit nanometer-RMS surface finishes? Talk to Lloyd.

Griffiths remembers the first time he talked with Lloyd. It was the fall of 2020, right after the first big makerspace interest meetings in one of the Brown-Kopel classrooms. Griffiths needed what they would call MAs — makerspace assistants — to help plan the procedures, the protocols and to even weigh in on what equipment they wanted. Approximately 30 masked students, some on campus for the first time in months, had shown up. In terms of their passion for the possibilities, the cream quickly rose to the top.

“There were a handful that stuck around after that meeting that became the core group that really got things going,” Griffiths said. “Cyrus was one of them. I remember when we were talking about the machining shop, he said he’d never been more excited about anything in his life.”

Sixteen months later, it’s easy to see why.

There he was, just a budding Auburn aerospace engineer from Atlanta fascinated with precision machining, looking to pass the pandemic with something more stimulating than constructing a LEGO Saturn V rocket, when he was struck with the urge to manufacture his own parabolic mirrors — the kind in telescopes. Just because, as a student in the Samuel Ginn College of Engineering who now had access to a Haas CNC Mini Mill 2, he could.

No, the makerspace didn’t have the diamond-turning lathe he would need to make the mirrors — very few universities do — but it did have the machines that could make the diamond-turning lathe he would need to make the mirrors. So, along with mechanical engineering senior Nick Browning, MA lead for the center’s manual lathe and the waterjet, he is.

It’s going well.

In November, the pair attended the annual meeting of the American Society of Precision Engineering (ASPE) in Minneapolis, connecting with representatives from Professional Instruments, an industry leader in ultra-precision manufacturing. Upon learning of Lloyd’s makerspace ambitions, the company offered two free Biconic air-bearing spindles — a key component in diamond-turning lathes — towards completion of the project.

“We hope to see a functioning lathe in a year or so,” he said. “It will allow us to produce parts to the same standards that commercial units can, but for far less money.”

And by “us,” he means Auburn. The plan, Lloyd said, is to add the lathe to the makerspace’s machining arsenal, furthering the facility’s capacity for research in areas such as optomechanics, aerospace and even just plain old physics. Lloyd, currently the MA lead for the CNC mill and manual mill, is also using the experience to apply for an undergraduate research fellowship. But the internship from KERN Microtechnik is already in the bag.

When, at the ASPE meeting, Lloyd and Browning told the CEO of the German-based CNC machine developer’s North American division about what they’d been doing outside the classroom for the past 10 months, he handed them his business card.

“They have an internship program where they pay for you to live in Germany at their factory for six months and independently work on a project to go onto their machines,” Lloyd said. “He said to email him whenever we want to do it.”

They both plan to.

“None of this would be possible,” Lloyd said, “without the resources at the makerspace.”

Stories such as Lloyd’s are exactly the sort Bob Ashurst wants to help write. In August, the Uthlaut Family Associate Professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering was named director of the Design and Innovation Center. While Griffiths focuses on day-to-day operations, Ashurst’s role is more big picture. Fundraising. Industry initiatives. Faculty engagement. Spreading the word of Auburn Engineering students just deciding to build a diamond-turning lathe in their spare time to folks up in Huntsville’s technology sector.

“Cyrus is nailing it,” Ashurst said. “I’ve always thought something like the Design and Innovation Center was such a good idea, and our hope is to help steward and shepherd those same sort of opportunities.

“To me, the best thing we can do for students is to give them hands-on experience using tools and getting a feel for what things are and how they work. Having an appreciation for what’s feasible. You just can’t do that from a textbook in a classroom.”

BUILDING A CREATIVE COMMUNITY

The tours will stop outside the prototype shop and people will point their cell phones at the acrylic, laser-cut X-wing fighter hanging in the window, courtesy laser cutter lead MA Joy Simmons. But when they come inside and get a real feel for what’s happening, woodshop lead MA Walt Gary can tell the appeal of the place extends beyond the cool toys.

“People are almost more excited to learn that everyone running individual shops within the space are just students that genuinely enjoy the work,” Gary said. “I think what makes them really want to be there is the desire for an unstructured creative community.”

And that, everyone says, is what they’ll get, thanks in no small part to Grace Kovakas and Anya McDaniel. After using the makerspace to build a fuel cell car for an assignment, per their professor’s recommendation, the chemical engineering sophomores couldn’t get enough.

“I was like, ‘this place is cool,’” Kovakas said, “We have to keep getting certified.”

They kept getting certified.

makerspace assistants in the Design and Innovation Center.

Kovakas is now lead MA for the prototype shop. McDaniel is lead MA for the laser cutter and wet lab.

“You can do anything here, you just have to have the right mindset,” McDaniel said. “If you’re just sitting at home thinking of ideas, and you’re like ‘oh man, I wish we could do that’ — well, in this environment, you can. But it’s still almost like this hidden treasure.”

McDaniel and Kovakas and plenty of others are helping turn the hidden treasure into a hangout.

The makerspace — the open layout, the interdisciplinary opportunities — is perfect for the sort of collaborations that can foster something close to a sense of family.

The student organizations, such as Auburn Off-Road and War Eagle Motorsports and the rocketry club, quickly began utilizing the center, but the teams usually kept to themselves. So would the senior design teams that started showing up. The machine shop folks mostly stayed in the machine shop. The woodshop folks stayed in the woodshop.

“I don’t know if you know this,” McDaniel joked, “but if you meet an engineer, they’re probably an introvert.”

McDaniel isn’t. She likes talking to people. (The hobby listed on her online Makerspace Assistant bio? “Rambling.”) She and Kovakas began asking people what they were working on. They started debates on whiteboards: Derivatives vs. Integrals — which is better? Defend your answer!

Before long, everyone was planning a trip to Six Flags.

“The aerospace boys wanted to go to the Huntsville Space and Rocket Center to stare at rockets,” she said. “I was like, ‘no.’”

When she’s not building community, she’s building a model of the B2 Spirit Bomber or an anniversary present for her parents. But McDaniel says the leadership experience the makerspace has provided has meant just as much as access to the coolest fabrication tools on campus.

Earlier this year, mostly just for kicks, she went to one of the college’s career fairs. She left with an internship offer from Ascend Performance Materials.

“They didn’t care about my grades,” she said. “They cared about the makerspace — that I was in charge of the laser cutter, that I had a team under me.”

The same thing happened for mechanical engineering junior Jose Arquitola.

“My experience working here is the sole reason I got my co-op at IS4S,” said Arquitola, lead MA for the electronics shop. “Seriously, they did not care about my grades — we spent the whole time talking about my time here. I had only heard of the makerspace before enrolling, but it has changed the course of my undergrad experience entirely.”

It’s about to change the course of Ethan Peat’s life entirely.

The metal shop lead MA is planning on modeling the ring in CAD, and then printing the model in castable wax resin on the Form 2 3D printer.

He’ll turn that print into a casting plaster mold that he’ll throw into the new kiln Ashurst helped procure — they’re calling that room The Bakery — for a 17-hour burnout cycle that will leave a perfect mold of the wax print.

Then it’s just a matter of melting the gold and pouring it in.

It’ll be a lot of work, yes. But he and Betsy just celebrated their four-year anniversary. And her family seems to like him.

It’s time.

“I don’t trust myself to set a diamond in there, though,” he said. “I’ll probably take it to the jeweler for that.”