Mechanical engineering professor David Dyer is retiring after the longest Auburn career of any faculty member in university history. The man they call Doc reflects on how things on the Plains have changed over the past 59 years — and how some never have.

There’s no real secret. He liked it — that’s it. He liked machines. He liked engineering. He liked students. He liked feeling that through his position in Auburn University’s Department of Mechanical Engineering — first as an assistant professor, then as an associate, eventually as chair from 1995-2008 — he made a difference each day — all 21,500 or so. He wasn’t trying to set a record. It just happened. At least, best anyone can tell.

Because if there’s a professor who’s taught longer — not just in the Samuel Ginn College of Engineering, but all of Auburn University — no one knows about it. George Petrie? Former engineering dean J.J. Wilmore? Rookies. Didn’t even pass the 55-year mark. Professor David Dyer — or Doc Dyer as they’ve called him for as long as anyone can remember? 59 years. His retirement, which went into effect May 31, closed the chapter on 59 years of teaching… at the same school, in the same department, in the same way. With the same values. Fifty-nine years of training young Auburn minds and hands to work skillfully. Fifty-nine years of just Doc being Doc.

Inspiration

Things started up in Tennessee in the 1940s, just south of Nashville, in a place called Eagleville. Population: not much. Doc would probably fancy himself the second-best engineer to come out of Eagleville. He’s good. But he’ll be the first to tell you — he’s no Dump Edmunds.

“The Wizard of Eagleville” — that’s what the Eagleville Times calls Edmunds every time it does a local history spread. Doc remembers him well. Is it safe to call Edmunds one of his inspirations?

“Oh, yeah,” Doc said.

He’d take a break from his farm chores, walk down to the grocery store and sit around listening to Edmunds “holding court,” talking about his inventions.

“He invented the dump truck,” Doc said with a smile.

Now, Google’s a little less certain about that than Doc. Whatever Edmunds’ contribution to the evolution of the modern dump truck isn’t quite as celebrated as, say, John Isaac Thornycroft or Garfield Wood. But, in Eagleville, that’s the story. In Doc’s mind, that’s the story. He’s sticking to it.

“That’s why they called him Dump,” Doc said.

Another inspiration? His uncle, Paul Fairfield. He had a lot of patents, mostly related to canning. It soon became clear to young Doc that farming might not be for him. And if you knew about machines — if you knew how they worked, which Doc always just seemed to — there might be another life available, or at least an easier one. So, when he asked his mom how he could be like Uncle Paul and do things like Dump, she told him the two magic words: mechanical engineering.

He started school at Middle Tennessee State University, paying his own way. They had a sort of pre-engineering pipeline program going with the University of Tennessee: get your basics out of the way, head to Knoxville. Which is what David did.

He got good grades. He met his wife, Angie. And he met Mancil Milligan.

Birth of A Teacher

If Edmunds opened Doc’s eyes to the wonders of engineering, then Milligan, a young University of Tennessee mechanical engineering professor who taught a class on boilers, opened his eyes to the wonders of teaching engineering.

“He’s the one who kind of got me going in that direction,” Doc said. “He was just good.”

Milligan, who is still very much alive at 92 years old — much to the surprise of his former student — says the same about Doc.

“I definitely remember David,” said Milligan, professor emeritus at the University of Tennessee. “David got it. He kind of helped teach some of the others.”

Yes — that was part of the charm of Milligan’s class, Doc said. It was almost as if Milligan taught him how to teach engineering.

Several of the boys would come by his room in South Stadium Hall and ask Doc to elaborate on Milligan’s instruction. It was almost like it was his own little class. Doc loved seeing the light bulbs go off. He knew it was for him.

He finished his bachelor’s in mechanical engineering at Tennessee. Then, he headed off to Georgia Tech for his master’s and doctorate, excelling there, too.

In 1965, geography was a big factor when it came time to hunt for a job. He interviewed at Vanderbilt. But the big city? No. He wanted something closer to home, if not on the map then at least in spirit.

He interviewed at the school across the state. He interviewed at Clemson. In the end, he got as close to Eagleville as he could — War Eagle Country.

“Auburn impressed me,” Doc said. “They had good students who were probably a little more ahead of the students at Tennessee. They had some good young faculty. They had good facilities.”

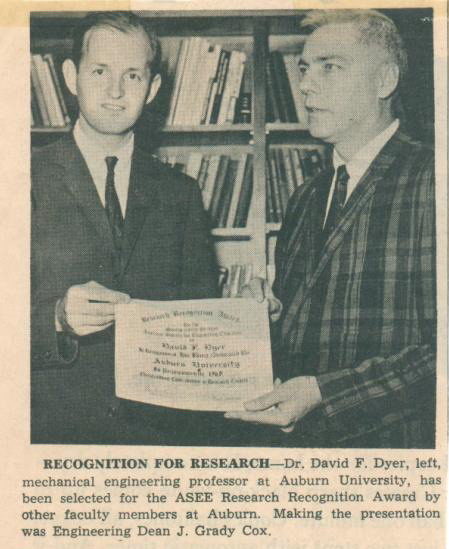

They even had a computer — one whole computer. You could walk down to the computer lab in Broun Hall, drop off the punch card with the numbers you wanted crunched, come back after lunch and hope for the best. Doc shook hands with engineering Dean Grady Cox, who told him that at 25 years old, Doc was the college’s youngest hire, or at least in modern memory. Doc packed his bags for Auburn.

Then he packed them for London.

Cold War, Hot Research

For Doc, another selling point for Auburn had been the luxury the college allowed professors when it came to professional development. He quickly saw it firsthand. Within a year of arriving at Auburn, he’d been offered a National Science Foundation (NSF) postdoctoral fellowship at Imperial College; Cox told him to go for it. He and Angie spent a year in London.

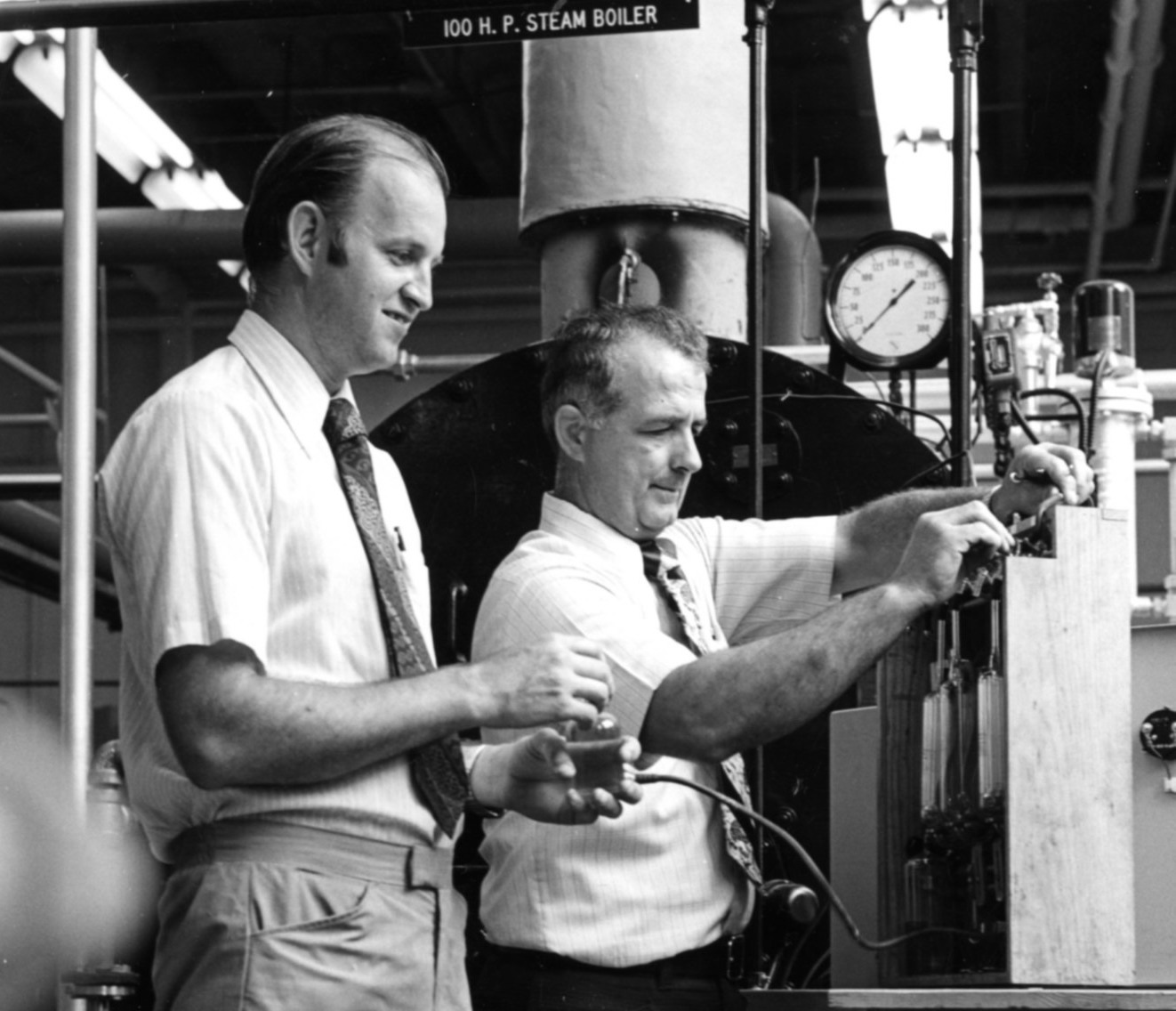

When he returned to Auburn, a new dimension of his still new job had opened up — research, important research, and lots of it.

It was the mid-1960s. The Cold War was warmer than ever. Though he hadn’t realized it when he accepted the fellowship, the professor Doc studied under, Brian Spalding, was the world’s leading expert in something Uncle Sam was growing increasingly interested in.

Suddenly, the young professor whose college research had focused mostly on freeze-drying knew as much as practically anyone in the United States about heat and mass transfer — the nuclear kind.

“I brought that knowledge back to Auburn, and we got several million dollars’ worth of contracts,” Doc said. “Back then, that was big money.”

And from big groups. The Army. The Navy.

“They wanted to know how you could fortify assets against nuclear blasts,” Doc said. “Me and Dr. Glenn Maples went to Washington, D.C. at least once a month for several years getting research support. We had it pretty good with the NSF and the Office of Naval Research. We did that work here for about 10 years.”

There was other work, too. Less life-and-death, but just as in demand. Maples and Doc soon formed a lucrative, nationally respected energy consultancy still operating today. Want to know how to conserve power? Call Doc. Want to do things with a boiler you didn’t think possible? Call Doc.

Doc’s colleague P.K. Raju, the Thomas Walter Professor Emeritus in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, would add one more thing to the list: want to get students interested in learning? Call Doc.

Doc’s reputation as a researcher was already well-established when Raju arrived at Auburn in 1984. What immediately impressed Raju, though, was how Doc leveraged it in the classroom.

‘I Just Liked It’

“Dr. Dyer’s consultancy projects and expert witness assignments endowed him with a wealth of industrial experience that he used to enhance the educational experience of students,” Raju said. “He has been a strong advocate for providing experiential learning opportunities within the department.”

Raju immediately points to the Auburn Engineering Technical Assistance Program, which earned national recognition and a significant NSF award for providing students real-world experience through technical assistance to industries in Alabama. Raju directed it. But Doc helped establish it, he said.

“Without him, it wouldn’t have happened,” Raju said.

Doc also helped Raju establish and develop the Laboratory for Innovative Technology and Engineering Education, which produced award-winning, real-world multimedia case studies for use in mechanical engineering classrooms.

For Raju, that was exactly the vision and leadership that made Doc an obvious choice to chair the department in 1995. Pradeep Lall, the MacFarlane Endowed Distinguished Professor and Alumni Professor, feels the same.

“Doc’s impact on education and research during his tenure as department chair and as a faculty member will continue to be felt long into the future,” Lall said. “But the thing that impressed me the most about Doc was his passion for student learning.”

That, said Lall, will be the image that sticks with him: walking through Wiggins Hall, looking over and seeing future engineers packed around Doc’s desk, asking questions, getting answers.

John Prunkl, a 1990 mechanical engineering graduate who chairs the Department of Mechanical Engineering’s Advisory Board, was one of those students. At Doc’s recent retirement celebration, Prunkl, who owns a Chicago-based energy company and has more than 30 years in the power industry, surprised Doc with news of a $25,000 scholarship the board plans to endow in his name.

In his mind, no mechanical engineering professor in Auburn history deserves it more.

“Dr. Dyer, there’s a good chance you don’t know who I am,” Prunkl said. “But when I go into power plants, when I’m looking at boilers, you’re there on my shoulder.”

Doc smiles at that. The feeling of someone always sitting on your shoulder — he knows it well.

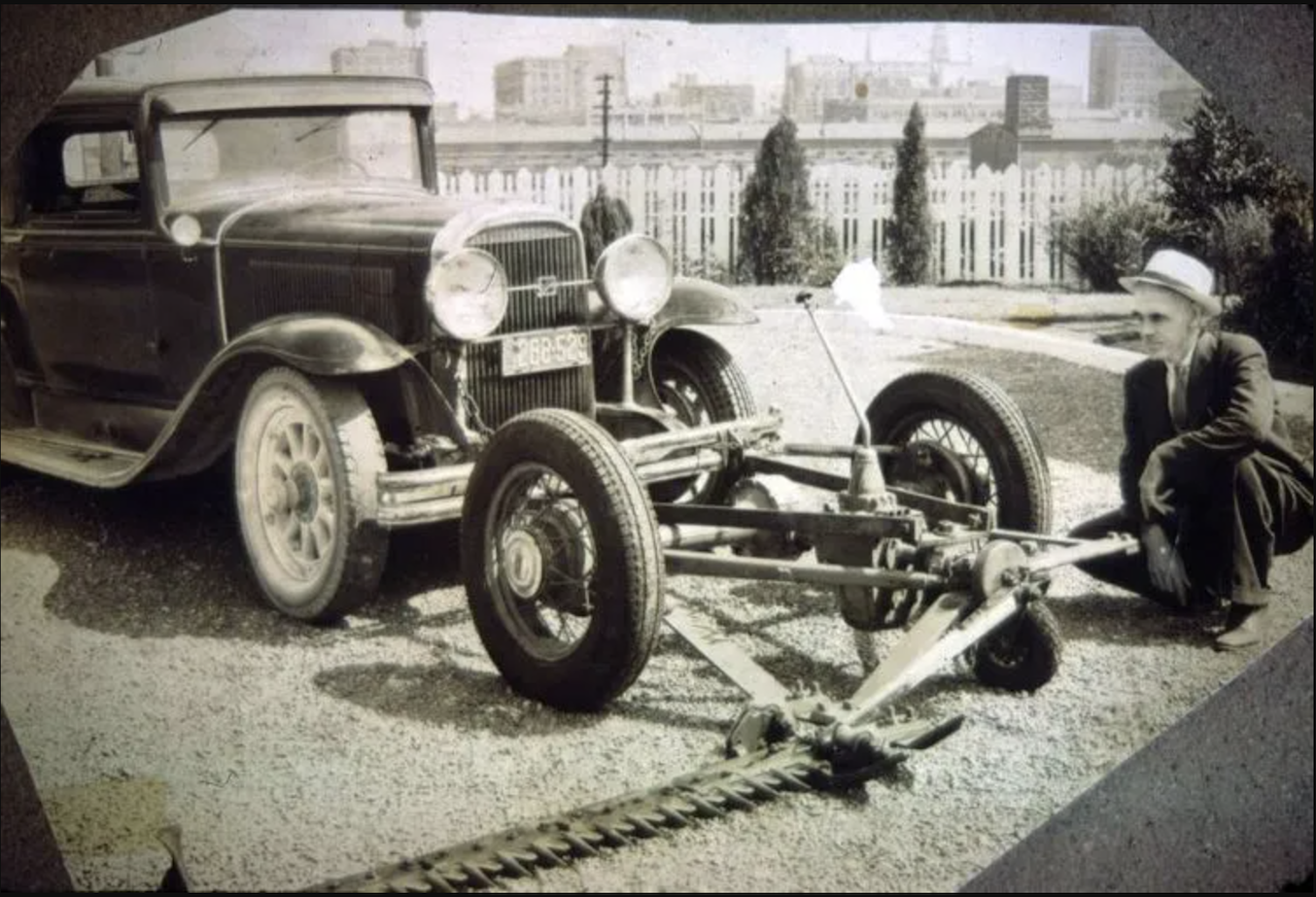

He’s yet to move out of his office. Old textbooks are still on the shelves. His old slide rule is still around somewhere. And there’s still that Xeroxed photo taped to his office door. He put it there a few months ago. It’s black and white — an old man squatting on the ground next to some sort of crazy contraption in the 1930s.

“You know who that is?” he asks. “That’s Dump Edmunds.”

Why did he put it up? He smiles.

“I just liked it,” Doc said.

That’s Doc’s answer for almost everything. Why didn’t he hang up the boots five years ago? Ten years ago? Twenty-five years ago?

“I just liked it,” Doc said. “I just like teaching.”

He remembers that first class like yesterday — Thermodynamics in Ramsay Hall.

His last?

“Thermo,” he said, “only it’s HVAC.”

So, what’s different now that the students can reach into their pockets for a computer rather than wait in line for the single machine in Broun Hall? What’s changed in 59 years?

Doc leans back in his chair. He thinks for a second.

“Not much,” he said.

Auburn students, he said, are still great students, same as always. They’re still respectful, same as always. They still want to make a difference. And he still likes giving them the tools to do it — the basics. The basics never change. Some things never do.

“Yeah, I may try to come back and teach another class or two,” he said. “If they’ll let me.”