The story of how Auburn Engineering helped light the way for the Auburn University Marching Band’s grand prize in the 2023 Metallica Marching Band Competition.

Corey Spurlin knew there was something special about that show. Whether it was the combination of night sky and stadium lights, the competition that inspired it or simply the music itself, the marching band director isn’t sure, but the atmosphere was electric on Oct. 21, 2023, as the Auburn University Marching Band (AUMB) took the field at halftime of the Auburn vs. Ole Miss game.

The performance was make or break. Night games aren’t easy to come by, after all.

“That’s the challenge that most people don’t really understand,” he said. “We take three or four months to plan one halftime show and get it ready. But we don’t find out game times until a week before. You plan all this, and then you might have an 11 a.m. kickoff. But this time, we actually got a night game.”

Wherever I May Roam

Let’s rewind to 2016.

Spurlin had just completed a stint as a judge for the state championship for Texas high school bands. One band stood out to him for using basic LED lighting effects. The idea had a lot of potential.

AUMB’s 2016 season of halftime shows was already set, but when the season came to a close and planning began for 2017, Spurlin wondered how Auburn might incorporate LED lights.

“I put out an all-call to the band. I asked for anyone with lighting experience, but especially electrical engineering majors, to come talk to me,” Spurlin said.

In any given year, roughly one-third of AUMB students are pursuing a degree in the Samuel Ginn College of Engineering — by far the highest percentage of majors represented among its 380 members.

“I think engineers are required to think outside the box in order to be successful, but they must also be very meticulous with their work,” Spurlin said. “And it’s the same with music and band — our students must be meticulous and precise with their work despite the way they feel that day or what outside influences may be impacting them. That crossover leads a lot of students who are very good musicians and band members in high school to also have an interest in the different fields of engineering.”

Two of the four current AUMB drum majors are Auburn Engineering students — Ross Tolbert, a chemical engineering junior, and biosystems engineering sophomore Bella Nonales.

“People tend to think that the marching band is made up of music majors, but that’s just not the case — we have people from all over,” Nonales said.

More than just a common college, AUMB engineering students have a built-in support system to carry them from performance to performance, class to class.

“It’s really cool that there’s an interconnectedness between band and engineering. I just love that,” Tolbert said.

biggest thing,” he said. “I think engineering and band both teach life skills like problem solving and working on a team.”

Master of Puppets

For Ben Brisendine, ’21 electrical engineering, designing lighting effects was a hobby.

His annual computerized Christmas light display was always elaborate and over the top.

“I got wind from one of my friends that Dr. Spurlin wanted to do some big lighting something that year, and I was like, ‘I know a little bit about that — maybe I should try to get involved,’” he said.

The task wasn’t just to light up the band. Spurlin asked Brisendine to take it to the next level.

“I wanted to program each person individually so that we could create different patterns and ripples and have it all perfectly timed with music. I didn’t know what would come of the meeting, but a student development team formed, and Ben took the lead on the project,” Spurlin said. “What Ben came back with was a prototype and a list of what we would need. He showed me how the battery packs and receivers would work. They were very smart with the design. They thought about how we could put the battery packs in the pockets of our main uniforms and run them down so the fans couldn’t see any of the wiring.”

Brisendine approached the project like the lighting designer he was. Utilizing LED strips, DMX dimmers, transceivers and other commercial off-the-shelf parts, he presented Spurlin with an option that could be easily ordered and replicated at scale.

Once in place, the system would be programmed on his laptop and wirelessly transmitted to each receiver, timed perfectly with the music and drills.

Brisendine’s technology was first deployed as part of a Las Vegas tribute show honoring the individuals killed at the Route 91 Harvest music festival the prior month. A show filled with lights for a city full of lights — a fitting memorial.

AUMB’s second show to incorporate the LED technology came after much-needed repairs and reworking of the equipment over the 2020 season lost to the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, Spurlin brought the lights back for a patriotic show — drill formations that lit up the Statue of Liberty in red, white and blue. Fireworks bursting with lights. An American flag rippling on the field.

“The disadvantage with the first two light shows was that we never really got a night game,” Spurlin admitted. “We were planning to do the 2021 show at the Mississippi State game, and we thought all year that it was probably going to be a night game. Then, it was scheduled for 11 a.m. We ended up performing the show at the Alabama game — it was a 2:30 game, so it was partially dark, but not to the extent we would have liked.

“With the Vegas and patriotic shows, the only way we could share our work with fans was to video with a drone at our practice field after dark and post it online,” he added.

Nothing Else Matters

The 2023 show will go down in AUMB history as the year it won the Metallica Marching Band Competition, “For Whom the Band Tolls.” What began as a discussion among band directors and drum majors evolved into a showcase of musical talent and engineering expertise that impressed the likes of Metallica’s singer James Hetfield, drummer Lars Ulrich, guitarist Kirk Hammett and bassist Robert Trujillo.

“I liked that this competition was going to have a panel of adjudicators select the finalists, and then the actual rock band itself was going to pick the winners,” Spurlin said. “That made it really a true collaboration between the rock band and what we do in marching band.”

The competition guidelines were simple — play original Metallica music for a chance to win $85,000 in prizes consisting of musical instruments and equipment. Once again, Spurlin was interested in using Brisendine’s lights to put AUMB’s best foot forward in the competition.

“Dr. Spurlin called saying, ‘Hey, Metallica is doing this big band competition. There’s a huge prize for it.’ I asked him, ‘So you want to get out the big guns?’ and he said, ‘I want to get out the big guns!’” Brisendine said.

Spurlin envisioned a heavy metal rock concert set at the 50-yard line and designed a show highlighting some of the band’s iconic songs brought to life with complex drill formations on the field.

“The drum majors had a meeting with the directors around springtime last year, and they brought up the competition. They asked us if we thought the band would be interested in doing something like this,” she said. “We were like, ‘very much so — yes.’ And then they brought up the idea of using the lights, and we were all in agreement that the lights would make us stand out so much.”

The show took two months to program. Brisendine worked with the War Eagle Productions and Jordan-Hare Stadium teams to integrate the field lights into the halftime show. The show was as big and complex as it could be on the hopes that the work, hard work of all involved would soon pay off.

Enter Sandman

Thwarted without a night game to perform its light show in 2017 and again in 2021, Spurlin and the AUMB decided that the third time must be the charm, risking it again in 2023, and the scheduling finally worked out in their favor.

“This time, we actually got a night game, and that’s one of the reasons, in addition to the competition and just the nature of the show, that I think it got so much more attention — it was a real night game,” Spurlin said.

The YouTube video of the performance was AUMB’s official entry into the contest, which married overhead drone footage with traditional sideline footage from the Oct. 21, 2023, halftime performance.

“We got to see three months of work turn into something that received a lot of press and a lot of attention, not only from the competition, but from people contacting our band directors telling them just how much they loved the show,” Tolbert said. “It really meant a lot to see people recognize the hard work that we’ve been doing and hard work that engineers have put into doing the lights and everything.”

In January, Metallica announced Auburn as the winner of the competition’s division 1 category, besting more than 450 schools across all competition divisions. AUMB also won the fan vote, earning an additional $10,000 prize.

“It really validated the students’ hard work. I see what they put into this each and every day, and they work really hard — you know, we were learning Metallica, but we were also learning two other shows at the same time,” Spurlin said. “I just really liked that they were able to experience watching ESPN that night, and hearing their name, and seeing their show on screen. They got a lot of good feedback throughout the season but nothing to the magnitude that we got from Metallica. Success always breeds success. So, for me, it just helps us continue to move forward positively.”

Showtime

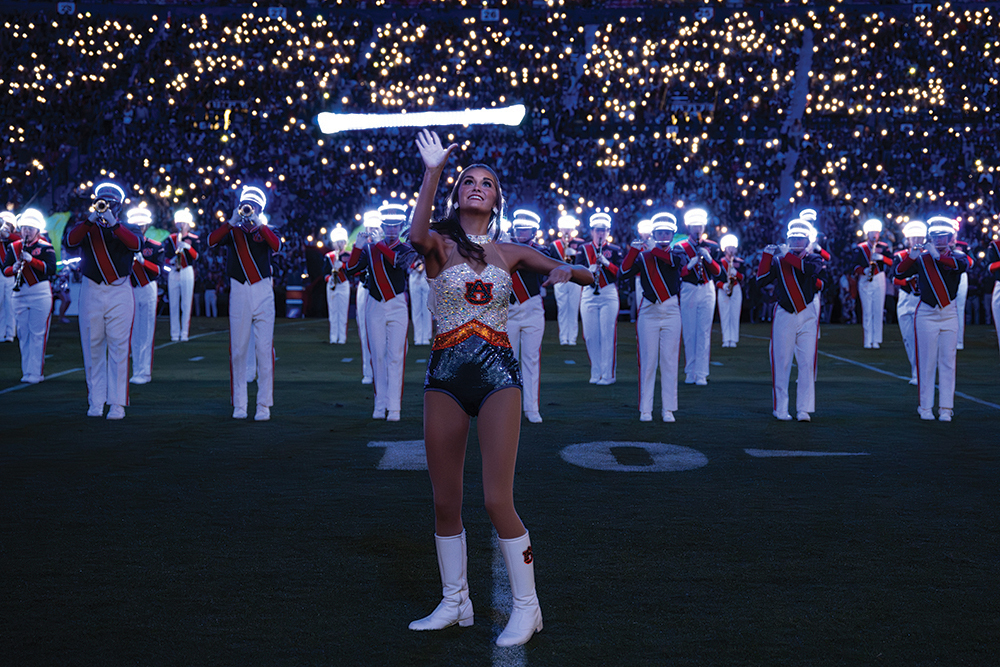

The lights dim in Jordan-Hare as the anticipation builds. As the first notes of Metallica’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls” chime, five bells of musicians come to life on the field, swinging to and fro as the lights that adorn their hats changed color with the music that fills the stadium. The show has begun.

As the marching musicians roam and play, their drill formations continuously transform from bells to music notes, flames to bolts of lightning striking in time with the music. The crowd roars its approval as the band spells out Metallica in its signature metal font. In the dimly-lit stadium, each marcher’s movement illuminates at just the right moment, allowing fans to savor the entire audio-visual performance.

A giant electric guitar materializes at mid-field, its 40-yard-long strings of light shredded by an invisible puppet master. Green and white rippling waves hum down the strings. A purple strobe effect emanates from center field, reverberating through the stadium. All the while, dancers, majorettes and colorguard twirl and spin illuminated flags and batons in sync.

On the field, symmetric spirals take shape as the white LEDs dance from hat to hat and pole to pole, and the music slowly builds to a powerful crescendo. Nothing else matters to the more than 88,000 fans in attendance at Jordan-Hare when the formation closes in on itself. Lines straighten and rotate on a dime, flashing blue as the music carries on to the finale.

The house lights match the marchers’ LEDs – everything aglow in red – as the formation undulates in and out from mid-field. All eyes are open and fixate on the blue and orange tiger’s face that stares back. Just as “Enter Sandman” rings through the audience’s ears, Sandman appears in front of them, blinking and alternating orange, blue and white. A finale’s finale.