Familiarizing first-timers with the concepts of chemical engineering can be a grind.

What happens when coffee beans are brewed at high pressures and temperatures? What happens when coffee beans are slow-roasted but ground coarsely and brewed with an AeroPress rather than a French press? Chemical reactions. Molecular breakdowns. Heat transfer. And ultimately… fluid mechanics that drip various samples into the awaiting mug. Some are strong. Some are smooth.

Each are unique.

Concepts of Chemical Engineering (CHEN 1000), a class housed within the Department of Chemical Engineering but open to all majors at Auburn University, takes students on a fundamental journey of making coffee while providing them with the basics of engineering principles through repeated experiments.

“When we talk about the engineering toolbox, students need to gain a better understanding of what is inside that toolbox and how to utilize those tools,” said Steve Duke, the Mary and John H. Sanders Associate Professor in chemical engineering, whose 11-student pilot “coffee class” in spring 2023 grew to 46 in just one year.

Duke hopes to exceed 100 enrollees by 2025.

“Inside any lab, students are designing a product and experimenting with different methods to meet the goal of their product’s attributes,” he said. “In this case, students are designing the best cup of coffee they can.”

Not just engineering students but College of Sciences and Mathematics students, business students… even a handful of music students.

The newly remodeled, 1,200-square-foot laboratory on the third floor of Ross Hall provides students with two bags of green coffee beans to experiment with — Ethiopian or Nicaraguan — both of which possess distinct flavors. Students roast, grind, brew, then, finally, sip.

“They roast (the beans) themselves,” Duke said. “They decide if they want a light, medium or dark roast. Or do they want a blend of different roasts? That’s one of the things they’re designing. What flavor profile are they working toward? How can they experiment with roasting the green beans at a variety of pressures, temperatures, lengths of roasting — and different brew methods — to achieve that? They control each of these variables, which provide hundreds of outcomes.

“Roasting is where the students learn about control variables, such as time, temperature and airflow. When a student sets up the roaster, they set the fan speed, the time and then the temperature. One might roast for five minutes at a medium temperature, and they’ll achieve a lighter roast,” he added.

Some consider this “first crack.”

“Another might roast for 10 minutes at a higher temperature or a lower wind speed, and they’ll get more of the darker roasts (second crack),” Duke said.

It’s Not Just Coffee — It’s Science

Roasting at different rates and temperatures impacts flavor.

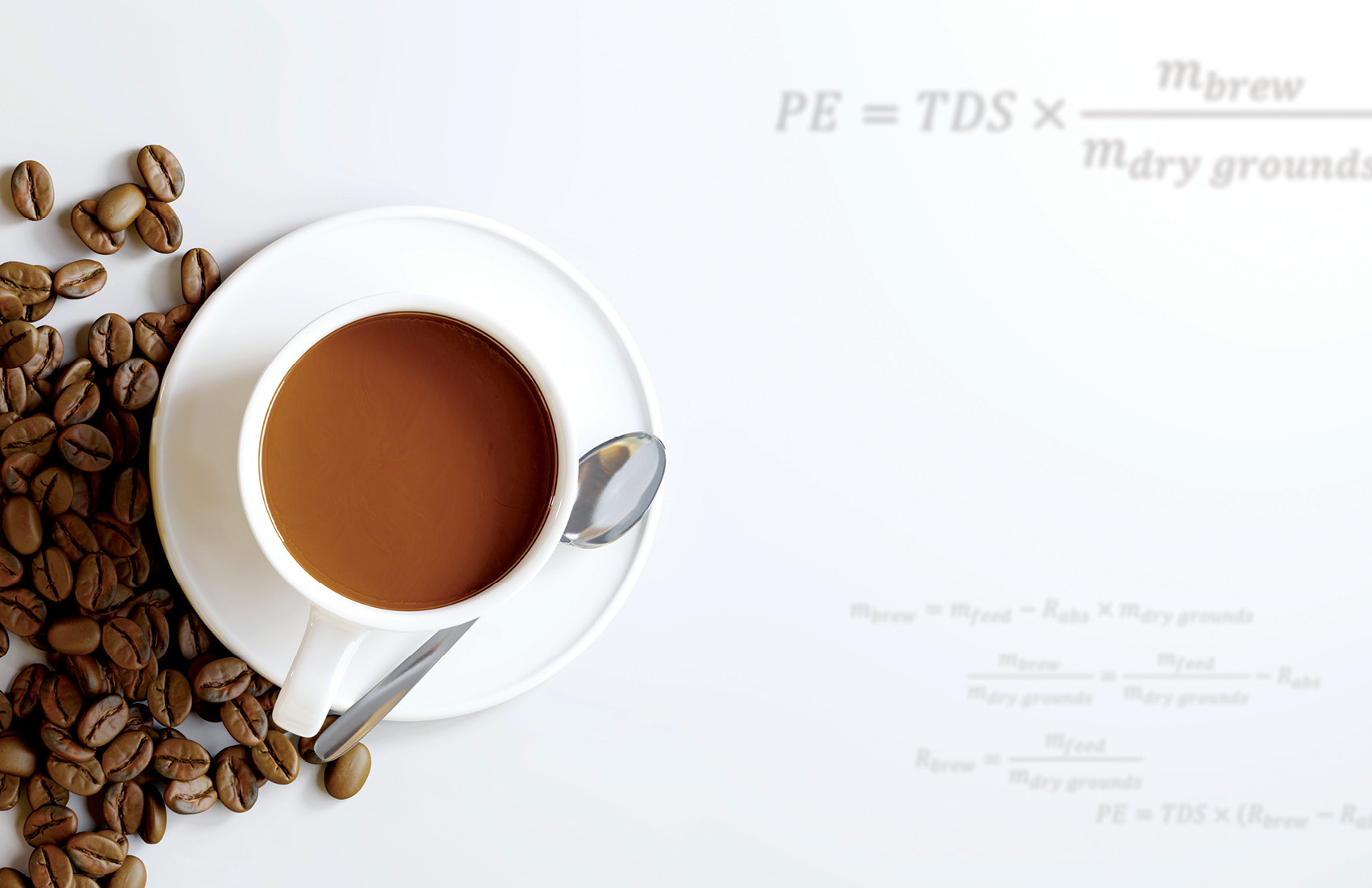

“This might sound more scientific than coffee-making, but water heating the grounds is extracting molecules out of the ground solids — and then putting it in the liquid,” Duke said. “The students learn a little bit about extraction and how temperatures affect it. Then they learn a little chemistry because they’re roasting beans and observing the chemical reaction that occurs during this process.”

Each time students create a cup of coffee, they must measure the energy in the water they’ve heated and the energy in the roast they used for the beans.

“In addition, students learn engineering concepts related to porous media — water seeping through the coffee grounds and then mass transfer in the brewing process,” Duke said. “What happens next when heated water hits the grounds? That’s when you’ve made a cup of coffee.”

Typical flavor varieties include floral, chocolate, lavender and dark, though all coffee creations are black with no cream, milk or sugar allowed.

“Everything you create in this class is unique to yourself,” said Luke May, a senior in chemical engineering who serves as Duke’s teaching assistant. “It’s easy to think that making coffee is easy before you get started. You add water to the beans, and you get coffee, right? But going through this class and these labs provides exposure to so many different variables and opportunities to tweak your formulas to make the coffee better, whether it’s in the way you roast, the way you brew, use water temperatures or how long you brew.”

Nicknamed the “coffee process lab,” participants are provided with eight lab stations, four sinks, four roasting stations (all covered by a 3×20 square-foot hibachi exhaust vent to control aroma), eight brewing stations and a variety of coffeemaking-related tools, including a French press, AeroPress, Clever Dripper and thermocouples for testing temperature.

“We also have pH meters and total dissolved solids meters, which measure how much of the fluid is solid,” Duke said. “For everything they do, they measure the energy of the process in kilowatts, and for product quality, they measure total dissolved solids and the percent of extraction. Also, how does the product rate on a taste test scoresheet? Do you like the brewed coffee?”

This is much more rigid than the old tried and true Mr. Coffee method.

“We have one of those, too,” Duke said. “But the students rarely use it.”

Why Coffee?

“Coffee makes it very approachable,” Duke said. “If I said we were designing something else, like a Q-tip, that wouldn’t draw that many people into the class.”

The class’s real genesis stretches far beyond the third floor of Ross Hall. It was born on the West Coast. “The Design of Coffee: An Engineering Approach” was the 2012 creation of William Ristenpart, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of California-Davis and director of the UC-Davis Coffee Center.

“About 10 years ago, I heard Dr. Ristenpart give a talk at the American Institute of Chemical Engineers, and I thought, ‘Oh, I really want to do that,’” said Duke, who has taught in Auburn Engineering classrooms since 1996. “I’ve always wanted to do something for students from all majors to expose them to engineering skills. I thought I would call it engineering literacy, which would have been a lot like financial literacy. Instead of learning the basics of finance, how to stay out of debt and balance checkbooks, etc., this would similarly be called engineering literacy — the basics of engineering, or some aspect of that. I even mentioned it to (Auburn University President) Chris Roberts, who was the college’s dean back then.”

Duke’s vision had to wait, however, as he became associate dean for academics, pulling him away from teaching for seven years. His presence in the classroom was missing. His desire to create a basics of engineering class was not. By the time Duke returned to Ross Hall classrooms in 2020 as associate professor, that original engineering literacy idea had the scent of roasted coffee.

“Dr. Roberts asked, ‘You’re probably going to start that coffee class, aren’t you?’ I replied, ‘I already am,’” Duke said.

‘You Learn With Imagination’

Luke May was one of the 11 original students in the pilot coffee class.

“This class helped me develop a better appreciation for basic engineering concepts and pushed me along as an undergraduate researcher,” said May, a member of assistant professor Symone Alexander’s bio-inspired materials laboratory. “I cannot stress enough how valuable this class has been to me and other students, who are provided with more tangible means to apply what we’ve learned. In many classes, you learn the information on paper. In this class, students learn by hands-on participation, which is extremely valuable.”

Though Duke’s idea was to educate and inspire, he takes pride in watching the students develop.

“You equip students with abilities, then provide them with space and freedom,” Duke said. “What’s great is you don’t have to force them to come to the coffee lab. They’re going to be excited about making the best cup of coffee they can.

“I’m hoping students can take what they’ve learned here and apply it to projects or tasks moving forward in whatever discipline they pursue. They might ponder, ‘There’s a concept I’ve developed, or a product or a goal that I want to achieve, and now I have some practices about how I might achieve that goal,’” he added.

It’s a win-win for students in engineering and across campus.

“It might mean they must experiment with a bunch of things, but that’s how you increasingly improve. You learn by the process of optimization. You learn by sampling. You learn by experimenting. You learn with imagination,” Duke said.