Paul Turnquist was in the 15th year of his 21-year tenure as head of Auburn University’s agricultural engineering department in 1992. Things were good. They had been good for a while. Some of the faculty’s recent research into alternative energy production via solar power and even animal waste was downright groundbreaking, the National Soil Dynamics Laboratory started by the department in 1933 regularly received national press, and his decision to transfer the department’s undergrads from the College of Agriculture to the College of Engineering was still paying dividends.

He’d seen the need for affiliation with the College of Engineering from his first day on the job in 1977. He finally pulled it off in 1985. It enhanced the curriculum and strengthened the department, just as he’d imagined. Still, he wasn’t satisfied. He wanted it stronger. More students. More involvement. More perspectives.

After all, it was the ’90s. Things were changing. They just weren’t changing fast enough for Turnquist.

“I was looking at SAT scores and student interests,” Turnquist said. “When you looked at female students, there was a high interest in biology, but a lower interest in engineering.”

That’s when it hit him.

“It seemed to me,” he said, “that to attract women into the department you’d need to develop a program that had those biological components.”

And to develop a name that accurately reflected them.

“In 2000, agricultural engineering made a generational change in deciding to change its name,” Turnquist said. “Our faculty were coming up with complex names, but I came to the conclusion that we should call it biosystems engineering. Short, sweet — biosystems.”

Turnquist’s campaign for change was reported in a 1998 issue of Progressive Farmer. Despite similar rebrandings happening across higher education at the time — many universities now refer to agricultural engineering as biosystems engineering — the news initially didn’t sit well with some, and not just locally.

“The word ‘agriculture’ is unfortunately perceived by most of the public as being very narrow,” Turnquist told the magazine.

The Victoria (Texas) Advocate’s editorial board responded to the article by accusing Turnquist of playing “name games” that debased the American farmer’s way of life.

“Do they (Auburn) think the food they eat is manufactured?” the paper asked. “Don’t they know farms and greenhouses provide the raw material retailed as fresh or processed food? That’s agriculture.”

Of course, Turnquist knew that. He wasn’t renouncing agriculture. He simply wanted to apply to the world at large the energies the department had previously spent almost exclusively on the farm.

He ignored the naysayers. Two years later, the Corley Building, home to biosystems, had new signs.

“Changing the department’s name didn’t come easy,” said Turnquist, who retired in 1998, “but it got done.”

And it worked. Enrollment increased. Diversity increased.

The decision’s only drawback?

All the questions graduates get asked.

Type “biosystems” into the search field on Dictionary.com and you’ll get “no result.”

Ask a biosystems graduate to define it, and you’ll get that smile.

“If I had a dime for every time I’ve been asked what biosystems is,” Rachel Helm said laughing.

Helm graduated from Auburn biosystems in the spring of 2017. She now works in New Orleans as a water and natural resources engineer for Stantec. She focuses on resiliency and sustainability, making sure life in the Big Easy can continue after the next Katrina.

“I kind of always answer that biosystems is a mixture of mechanical, chemical and civil engineering with a focus on natural and biological systems,” Helm said. “I always end up translating that to biosystems uses engineering methods and problem solving to mimic, alter and improve natural systems to help us in our day-to-day lives.”

Of course, you could have said the same thing when the department was officially organized in 1919.

Most of the researchers from the land-grant schools who attended the 1926 Southern Rural Electrification Conference in Montgomery, the first of its kind, went home green with envy. The possibility of boosting farm production via the miracle of electricity was still purely theoretical in every state in the union — every state but one. Alabama had already been at it for two years thanks to the research and resources of Auburn’s new agricultural engineering department and its partnership with Alabama Power.

The headlines that ran across the region in January 1924 said it all:

“API JOINS POWER COMPANY IN PLAN TO ELECTRIFY FARMS, WILL PUT ALABAMA IN FRONT.”

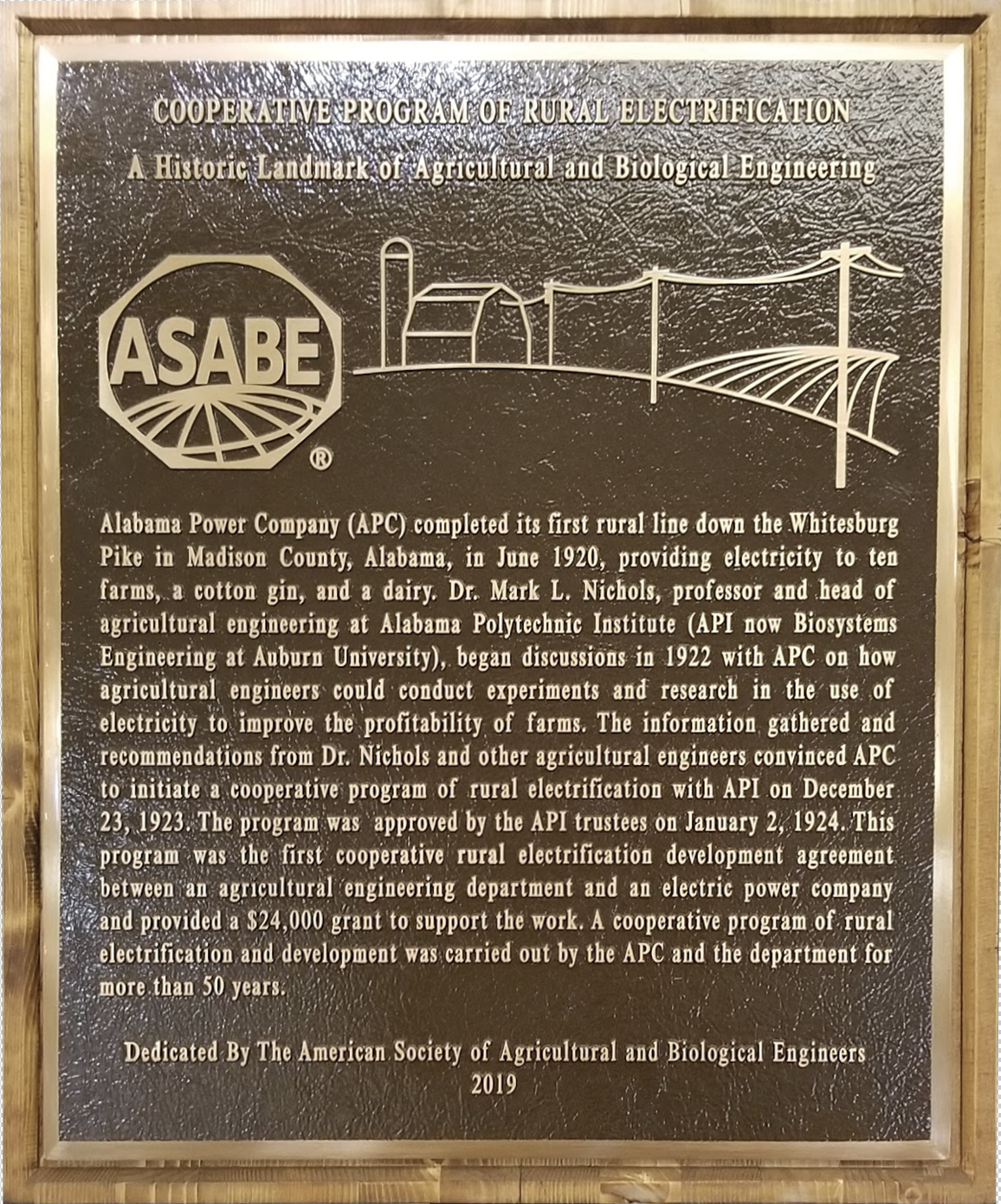

“This program was the first cooperative electrification development agreement between an agricultural engineering department and an electric power company and provided a $24,000 grant to support the work,” reads the plaque celebrating the historic achievement that the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers dedicated during the department’s centennial celebration in April.

That program lasted more than 50 years and helped hundreds of thousands of farmers across the state and beyond.

The name may have changed, but the 100-year story of Auburn Biosystems has stayed essentially the same throughout its phenomenal first century.

“Rural electrification was huge in the development of agriculture in the south and in Alabama, and agricultural engineering played a big part in that,” said Perry Oakes, Alabama’s former state conservation engineer for the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. Oakes earned his undergraduate degree in biosystems engineering from Auburn in 1978 and his master’s degree in 1982.

Proud as he is of the department’s early accomplishments, Oakes is also quick to point out its more modern success stories. Ever wonder why Alabama tops poultry production lists? The Auburn biosystems engineers who spent years developing better environmental controls for chicken houses don’t.

“The National Poultry Technology Center was created at Auburn, and a lot of that effort was centered in the biosystems engineering department,” Oakes said.

The department also initiated cooperative programs with the Forestry Department and the USDA Forest Service to enhance the repertoire of forest machine systems and minimize their environmental footprint.

“But in more recent times, the focus on bioenergy has been big,” said Oakes.

Where it once took energy to places no one thought it could go, Auburn’s biosystems engineering department now helps produce energy from places no one knew it existed: trees, grasses, algae and any other resource the department’s Center for Bioenergy and Bioproducts has been able to tap since opening in 2007.

“All of us want safe and plentiful food to eat, pure water to drink, reliable energy sources, and a safe and healthy environment in which we want to live,” said Oladiran Fasina, current head of Auburn’s biosystems engineering department.

“However, the methods that we will use to provide these life essentials for the projected 9-10 billion people in the world by 2050 will be substantially different from those of the last 100 years. I feel confident in the ability of this department and Auburn University to meet these challenges and to be a leader in providing engineering-based sustainable solutions.”

In other words, what the agricultural engineering department once did primarily for farmers, the biosystems engineering department is doing for the population as a whole — and with students and alumni who more accurately reflect that population. The current percentage of female students enrolled in the College of Engineering stands at around 20%. But walk into the Corley Building, and approximately 40% of the engineers you’ll see will be women.

Thank goodness for Turnquist’s “name games.”

You can hear the pride in his voice.

“The department is rapidly growing,” Turnquist said, “and that information clearly suggests to me that we have assembled an excellent faculty and that they’re heading in the right direction.”