The world can be a dangerous place. And anyone who doubts that we could be safer or more secure in it — in our homes, schools, offices and in our skies — should simply look to the headlines.

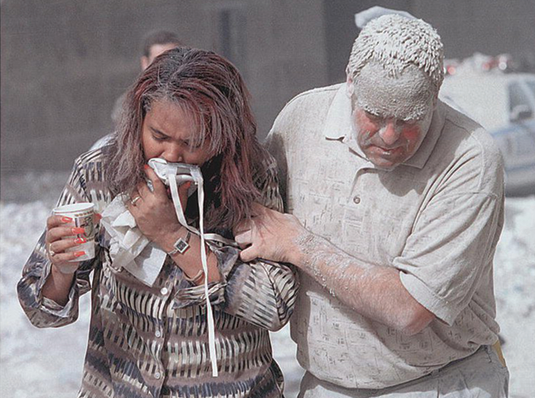

In September, the U.S. solemnly remembered the tenth anniversary of our country’s worst homeland attack since the bombing of Pearl Harbor. And while politics and religion and war are typically matters in which we are all individually invested, how we solve our problems — problems of safety, tools and technology that protect us — are challenges often left to engineers.

During the years since 9/11, the ways and means by which many engineers address those challenges have evolved with the times, and with changes in policy, our interests and our needs. How and why funding reaches certain projects is a science in and of itself, but the catastrophic events of September 11, 2001, have shown us that we still have a number of areas where we lack sufficient defenses and that research being conducted at the university level may offer the next generation of protection.

THE “T” FACTOR

Chemical engineering faculty member Mario Eden will tell you that chemical process design has not fundamentally changed during the past 10 years. But he will also tell you that the logistics involved with producing chemicals has caused us to face unprecedented challenges where the potential for a terrorist threat is concerned.

Eden’s area of expertise — high-value chemicals, renewable fuels and sustainable energy — was not new following 9/11, but the impact of the attacks on his work, and his field, is a real one. Though it is a result of strained relations in the Middle East more than the tragic loss of American lives, the impact of national security on his research area has affected design, accessibility and safety, as well as renewed American interest in generating chemicals from domestic resources.

“We began thinking about the safety of storing large amounts of flammable liquids and hazardous materials,” says Eden. “Now, you have to consider security threats, whereas before you primarily dealt with issues of environmental compliance. For design, we end up asking questions like, ‘Should there be less solvent,’ because of those safety concerns.”

Eden says that he feels this evolution of his research area was most likely inevitable, but that September 11 was a catalyst for safety and security becoming a top priority in research. It also shaped a new element researchers were forced to consider when developing chemical processes: a terrorist attack.

INFORMATION ASSURANCE AND COLLABORATION

Rodney Robertson, a 1980 electrical engineering graduate, is the executive director of Auburn University’s new Huntsville Research Center. His more than 30 years of work in federal science and engineering programs has offered him an inside look at the challenges we face as a nation in making our world — and the things in it — faster, stronger, lighter, less expensive and more secure.

As the former director of the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command’s technical center, he understands the importance of secure communications and the role that protected information exchange plays not only in our military actions but also our day-to-day lives.

“There is a general feeling in the defense community that the next big attack will be cyber,” says Robertson. “As a result, we are seeing increased funding for research to enhance the security of our communication, transportation, power, water and sanitation systems, health systems, banking systems and computer systems.”