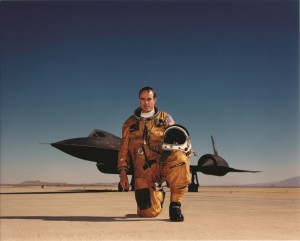

Do the math, Auburn engineers, and tell us how fast this is: Ed Yeilding flew from St. Louis to Cincinnati in eight minutes and 32 seconds . . . and no, that’s not a misprint. The answer is 2,190 miles per hour, a record that will stand the test of time. It was just one leg of a trip that saw numerous records set as Lt. Col. Yeilding flew the last flight of SR-71 Blackbird tail number 972, from coast to coast to its current home in the Smithsonian.

Do the math, Auburn engineers, and tell us how fast this is: Ed Yeilding flew from St. Louis to Cincinnati in eight minutes and 32 seconds . . . and no, that’s not a misprint. The answer is 2,190 miles per hour, a record that will stand the test of time. It was just one leg of a trip that saw numerous records set as Lt. Col. Yeilding flew the last flight of SR-71 Blackbird tail number 972, from coast to coast to its current home in the Smithsonian.

Some of the other records that he set that day on March 6, 1990, were Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., in 64 minutes, 20 seconds; and coast-to-coast, from Pacific to Atlantic, in 67 minutes and 54 seconds. Most of the historic flight was at Mach 3.3, the operational limit of the Blackbird that he flew with Lt. Col. J.T. Vida, the reconnaissance systems officer seated behind him.

A former F-4 Phantom pilot, Yeilding shows none of the braggadocio you might expect from a fighter pilot. The Florence, Alabama, native is quiet, polite and self-effacing. He points to the records that went into the books on that March day 25 years ago as a team effort that involved not only himself and Vida, but also the ground support crews, the engineers, and the technicians who worked on the plane during its secret Cold War missions.

Although the 1972 electrical engineering graduate first heard about the SR-71 program when he was a 15-year-old living near the end of Cypress Mill Road, up the hill from Cypress Creek in Florence, it really all began at Auburn. His father, William E. (Bill) Yeilding, attended Alabama Polytechnic Institute on the GI Bill after he was released from the Navy following Japan’s surrender in the Pacific, where he served as a Seabee. Bill brought his new bride, Carolyn, with him and graduated in electrical engineering as well, earning the first college degree in the family in 1949.

“I always admired my dad and the three years he served in the war, and the determination he had to earn a degree at Auburn despite huge obstacles,” Yeilding recalls. “Housing was extremely hard to come by, so he ended up converting a three-sided dirt floor garage into an apartment, doing most of the plumbing, electrical, concrete and carpentry, with a little help from his dad. My mom had a job at Drake Infirmary as a registered nurse, and that’s where I was born in ’49.”

Following his graduation, Yeilding’s father began a 35-year career with TVA in Florence, and his son grew up as a staunch Auburn fan.

“My dad said that I could go anywhere I wanted for college, but he would help pay for Auburn,” Yeilding points out. “Not that it was ever an issue – I always knew I wanted to go Auburn. In addition to engineering, I wanted to be at a school that had Air Force ROTC.”

Yeilding began his studies in 1967 in aerospace engineering, but got cold feet when he saw the huge fallout in the profession when the race to the moon ended. Nevertheless, he learned to fly a Cessna 150 with the 35 hours of flight training that ROTC offered, and paid for an additional hour and a half in the fall of 1971 so that he could become certified as a private pilot.

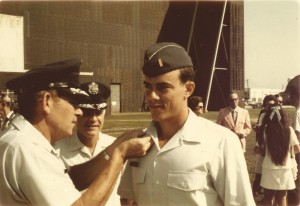

“I felt that I would have more flexibility and job security at the time with a double E degree, and while my first co-op assignment was at the Arnold Air Force Base research center in Tullahoma, Tennessee, I did later co-op terms at TVA’s Cumberland steam plant, close to Clarksville, Tennessee,” Yeilding notes. “Then, in the summer of 1972 at Charleston Air Force Base in South Carolina, Col. Robert Merritt, then AFROTC commandant at Auburn, pinned my bars on me and I was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Air Force.

“Vietnam was winding down and there was an overage of pilots, which resulted in a six-month delay in my first assignment,” Yeilding remembers. “I returned to Florence and practiced electrical engineering to fill in the time.”

He was called to active duty at Williams Air Force Base in Phoenix, and began a year of training in T-37s and T-38s, where he was fifth in his class. He then transitioned to the RF-4 Phantom and an additional six months of training. It was Yeilding’s first experience with reconnaissance aircraft – hence the “R” in the Phantom’s designation.

It was an experience unlike the high altitude SR-71 he would later fly. The RF-4 was used for high speed, low altitude photography – 550 miles per hour at 500 feet, with no GPS to help. As Yeilding explains, it was all about your ability to read a map, hold a precise heading and air speed, and make split-second navigation decisions. He would be based in Texas, Okinawa and Osan Air Force Base in South Korea for the next five years before returning to Valdosta, Georgia, to train on the F-4E fighter. In all, he spent nine years flying F-4s.

During all of this time he had his eye on the SR-71.

“I worked extra hard during those years, because I wanted a shot at it,” he said. “It came in 1982 when I was asked to come to Beale Air Force Base in California. I interviewed for a week. This included a flight physical, flights in a T-38, and sessions in an SR-71 simulator to see how fast I could pick up on instruction, procedures and the instruments in the cockpit. It was so different.”

Different, he said, because no other plane flew at Mach 3 speeds, or even close to it. Total familiarization of the cockpit was needed because there were no second chances at 80,000 feet, so Yeilding would spend 100 hours over a six-month period in simulators to build his confidence to the point where he could take care of any kind of emergency.

He would fly 93 overseas reconnaissance missions at the height of the Cold War, from 1983 through the retirement of the aircraft in 1990.

“We flew out of Beale Air Force Base in California, Kadena in Okinawa and RAF Mildenhall in England,” Yeilding explains. “That gave us access to all of the northern hemisphere, really with a worldwide reach, because the southern hemisphere was not perceived as a source of threats that required the kind of reconnaissance that we flew.

“All of the SR-71 pilots, all of the crews and all of the support people, they knew we were performing a vital mission – the surveillance we undertook was used by our leaders to make national defense and policy decisions.”

Those flights are still classified. But his last run, from ocean to ocean, is one he can talk about. Here is his first-person account:

We started to suit up one and a half hours before the flight. The pressure suit was composed of five layers and the team had to make sure that it would hold pressure, as well as check the comm system, connect the antifog filaments in the helmet, and a number of other things.

I remember that day so well – March 6, 1990. I got up at 1 a.m., got to my briefing at 2 a.m., and into the suit and onto the flight line at 3:45. We planned our takeoff for 4:30 – it was 7:30 in Washington – from Palmdale in the company of a small crowd that gathered for the last flight.

Pre-flight took about 30 minutes, with a systems check and engine start. We taxied down the runway, and I lit the afterburners, always a real kick in the pants. I raised the nose at 180 knots, and lifted off at 210. The gear had to go up immediately, because the landing gear doors were only rated to 300 knots.

We would be at 25,000 feet inside of 2 minutes – that’s about 5 miles in altitude.

The first thing that we had to do was air refuel – the routine was to take off with half a load of fuel for safety, so we’d be light enough to climb in case an engine failed just after lift-off. At 27,000 feet, we did that, with a couple of KC-135Q tankers over the Pacific Ocean. Then, with a full load, we turned east, lit the afterburners, and had a 200-mile running start as we accelerated. Fuel was very tight for the coast-to-coast flight, so we planned to cross the West Coast accelerating through Mach 2.5 at 63,000 feet, before reaching our cruise speed at 76,000 feet.

The first thing that we had to do was air refuel – the routine was to take off with half a load of fuel for safety, so we’d be light enough to climb in case an engine failed just after lift-off. At 27,000 feet, we did that, with a couple of KC-135Q tankers over the Pacific Ocean. Then, with a full load, we turned east, lit the afterburners, and had a 200-mile running start as we accelerated. Fuel was very tight for the coast-to-coast flight, so we planned to cross the West Coast accelerating through Mach 2.5 at 63,000 feet, before reaching our cruise speed at 76,000 feet.

As we crossed the West Coast in the early morning twilight, I could see the white ocean breakers all along the California coastline and the millions of lights of Los Angeles below me, as well as the lights of San Francisco and San Diego. Mexico, on my right beyond San Diego, was dark. As the sun came up, we were doing Mach 3.3, and I soon saw Vegas, Lake Mead and the Grand Canyon from 78,000 feet. I glimpsed Pike’s Peak as I passed the Colorado mountains, and Vida and I were soon over farmland.

It hit me again that we were crossing country in minutes that took months for our pioneers to do 150 years earlier. I really reflected in this flight what a great country we had – and all of the courage, the prayers and the sacrifices of our forefathers.

As we flew over the eastern part of the country, everything was in undercast (ed. note: overcast from the ground), but as I passed over the East Coast I got one last view of God’s earth at 83,000 feet. I thought about that too, and how I loved to fly this plane, seeing the slight, but noticeable, arc of the curvature of the earth; the darkness overhead; and the bright blue band of atmosphere over the horizon that was 400 miles from us.

We had flown coast-to-coast in 67 minutes and 54 seconds, and from L.A. to D.C. in 64 minutes, 20 seconds. Our average speeds were over 2,125 miles per hour for the former, and 2,145 for the latter.

We overflew Wilmington, just below Philly, and were still supersonic in a descending left hand turn, heading toward Washington. When we became subsonic we met another KC-135Q and took on more fuel at 25,000 feet. At Dulles International we made two low passes, one with afterburner, near the crowd that was waiting. We wanted to give them a look at the shock diamonds in the glowing afterburner plumes, and before landing, rocked the wings in salute.

I deployed that big orange drag chute . . . for this last time. My excitement in flying the highest and fastest plane ever was mixed with some sadness on this day because it was our final flight in the Blackbird.

Even now, from the vantage point of 25 years, Yeilding looks at the SR-71 not only as an aircraft, but also as an engineering work of art that has amassed a huge fan base, and that still looks futuristic even though the design is 50 years old.

After Yeilding’s SR-71 was retired to the Smithsonian, he pulled a five-year special duty assignment at Andrews Air Force Base, flying government VIPs around the world. Following his retirement from the military, he flew for Northwest Airlines, and after its merger, with Delta. He flew a number of different commercial aircraft, most noticeably the 747-400 on Japanese routes out of Detroit.

“Actually, I have enjoyed all of my assignments during my 34-year flying career, and I credit my Auburn degree in becoming one of two SR-71 test pilots able to work with the engineers at Lockheed Martin and other contractors in developing new equipment and software for this amazing plane,” Yeilding beams. “I’m proud to be an Auburn graduate . . . proud of my hometown of Florence . . . and I feel extremely blessed and thankful for all of the special people who helped me along life’s way during my boyhood and career.”

Two days after they landed in Washington, Yeilding and Vida were seated separately in coach on a United 767 flight returning them to California. As they taxied out of Dulles, the pilot told the passengers over the intercom that they were seeing the very SR-71 that had been on the news that week for setting a new transcontinental speed record.

“The woman next to me said, ‘It was worth coming to Washington just to see that plane,’” Yeilding recalls, “and I told her, ‘Yes, ma’am, it sure was.’”

And that was it.

The SR-71

The SR-71

• Constructed primarily in titanium – aluminum would

have been too soft for the SR-71’s fuselage

temperature, which reached an average of 550 degrees cruising at 80,000 feet, despite an ambient temperature of minus 70F

• Relatively fragile – although it could take on 80,000 pounds of fuel, it was designed to be light in weight, and could not take more than 1.5 G in supersonic turns, in an era when Yeilding’s F-4 could easily handle a 5-6 G ‘yank and bank’

• Only a 90-minute range on a tank of JP-7 – which would take it more than 2,500 miles; special KC-135Q tankers were required for in-flight fueling of the hungry J58 engines that burned 5,000 gallons of fuel per hour at cruise. The sea level thrust was 34,000 pounds each

• Fuel tanks on the SR-71 leaked like sieves, because the bottom of the tank was also the bottom of the wings and fuselage, which were constructed with expansion joints to handle high heat loads in supersonic flight

• Contrary to some popular lore, the SR-71 was ‘easy enough to fly,’ according to Yeilding – but required a sharp and constant eye on highly complex systems in a cockpit crowded with gauges

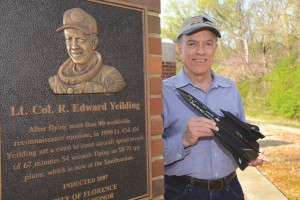

Lt. Col. Ed Yeilding is recognized

Lt. Col. Ed Yeilding is recognized

• In the Florence, Alabama, Walk of Honor located near the Marriott Shoals Hotel

• In the Florence Veterans Museum, which features an F-4 exhibit

• On the city street leading to the museum, known as the Lieutenant Colonel R. Edward “Ed” Yeilding Parkway

• In the Alabama Aviation Hall of Fame at the Southern Museum of Flight in Birmingham

• His military awards include three Meritorious Service Medals, four Air Medals, three Commendation Medals, and four Combat Readiness Medals

The SR-71 Yeilding flew to Washington is located

• At the Smithsonian Institution’s Udvar-Hazy Center, located near Dulles International Airport; other SR-71s are:

• At the Air Force Armament Museum adjacent to Eglin AFB in Ft. Walton, Florida, and

• At the Air Force Armament Museum adjacent to Eglin AFB in Ft. Walton, Florida, and

• At the Strategic Air and Space Museum located near Omaha, Nebraska

• The U.S. Space and Rocket Center has a Lockheed A-12 on display, a closely related airframe flown by the CIA prior to the SR-71 program

• There is also an A-12 Blackbird on display at the USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park in Mobile, and at the Southern Museum of Flight in Birmingham

Pingback: SR-71 pilot tells the story of when he and his RSO set four speed records flying from L.A. to D.C. in less than 65 minutes during their final flight in the Blackbird - The Aviation Geek Club

Pingback: SR-71 Spy Plane: Los Angeles to Washington, DC in 64 Minutes | taktik(z) GDI (Government Defense Infrastructure)